Mardi Jo Link – Bootstrapper!

Successful authors are usually loath to risk alienating the loyal readers they have worked so hard to acquire, so any foray into another genre is usually done under a pen name. But as with many things in her life, Mardi Jo Link isn’t one to do something just because “that’s how it’s done.” Already a successful true crime writer with several books to her credit – including one NYT bestseller – in 2013 she turned away from crime to pen the fascinating memoir “Bootstrapper: From Broke to Badass on a Northern Michigan Farm,” the story of her struggles to save her farm and raise her three sons in the wake of a devastating divorce.The book won numerous regional awards and has been optioned by Hollywood superstar and Academy Award winner Rachel Weisz. She has written one other memoir and is currently working on a new true crime project. I sat down with her recently to talk about her work, movie options and the joys and challenges of crossing genres.

Open Mic: You started in the genre of true crime. How did you decide to start there?

Link: That’s interesting because I was trying so hard to write a mystery novel. I had these grandiose ideas of it becoming a series and it just didn’t. It wasn’t exciting to me. The writing wasn’t good and it was as though I couldn’t even create good writing. I think I could recognize good writing so at least I knew enough to know mine was not there. I was lamenting about that to a friend and the friend pointed at the stack of books I had sitting in my ‘to be read’ pile and it was almost exclusively true crime, and the friend said “Why are you writing fiction when this is what you’re reading? Have you ever thought about writing true crime?” I hadn’t thought about writing it myself, which seems so ridiculous to me now. I had been a newspaper reporter, I had covered crime, I read a bunch of true crime and I was an avid watcher of Court TV – so I had the chops to do it but it just never occurred to me that that is what I should be doing. So I said ‘Well, there is this one case that I’ve always been curious about and there isn’t a book on it” and they looked at me like “do I need to connect those dots for you? Here’s a marker.” So I wrote an email to the University of Michigan Press and said ‘this is who I am, this is the book I’d like to write and are you interested?’ I didn’t have an agent and I didn’t know anybody at the University of Michigan. I actually graduated from their arch rival, Michigan State University. I got an email from their associate publisher and they said “yeah, we’re really interested in this.” I later found out that the associate publisher’s husband was an avid reader of true crime, so that was a stroke of luck that I couldn’t have anticipated. She told me to go to their website and read up on what they wanted in a proposal and to send them one. I did and they mailed me a book contract. You could talk to a thousand writers and you would never hear that story, so I count myself as incredibly lucky.

Open Mic: Yes, but also clearly prepared. What’s the saying, “80 percent of life is showing up.”

Her debut true crime story

Link: True. I didn’t have an agent and I’d never even written a book proposal before but I happened to have a case that nobody had written about that was quite famous, at least in the Midwest, and that was coming up on the 40th anniversary of the crime when there was going to be a lot of media attention around it. And on top of that, the publishers’ husband was an avid reader of true crime and said “I’d love to read a book on that case!” So all of those things fit together into me getting my first book contract in 2007. That book, “When Evil Came to Good Hart,” came out in 2008. It sold pretty well, is still in print and they’re going to release a 10-year anniversary edition in 2018 with a new forward. So that led to my publisher asking “Are there any other dead bodies up there in Northern Michigan that you’d like to write about?” That became book number two.

Open Mic: Is that what you thought you would be doing from that point forward?

Link: Well, I discovered that I loved the process, that it was just incredibly satisfying. The idea of finding a story in old documents and libraries and police files and newspaper clippings and then taking all these pieces and putting it together in a single, hopefully logical narrative in a way that nobody had done before and having other people besides me be interested in that was really exciting. It allowed me to use some of those reporter skills that you develop over a career. As a reporter you learn skills while working that you never learned in school or by reading books, only in the act of doing it. With the second story though, I was in the process of recovering from a divorce. I was a single parent with three sons and so I thought I was being smarter this time in selecting a case to write about that was geographically closer to home. So it was about 20 minutes from my house, the reverse of the first case I picked which was in the Detroit area which was five hours away. So I thought I was being practical in picking a case that was close to home, but it turned out that almost all the documents I needed to access had been stolen from the local courthouse and I needed to drive all the way to South Bend, Indiana which was even further afield than the first case. But you know the reporter goes where the sources are. You physically put your body where the physical documents are so that you can read them. So it turned out to be more involved in that way, the research part, than I had anticipated, but sometimes that leads to writing a book.

Open Mic: Are there new stories like this that you’ve already got your eye on or are working on?

NYT Bestseller

Link: It’s been interesting to me that people enjoy the memoirs – and certainly “Bootstrapper” elevated my profile in the way that the first two crime books did not – but I wrote a third true crime book called “Wicked Takes the Witness Stand” that’s 425 pages. It was a university press book and there’s very little redemption at the end, and yet that is the only book out of all five of mine that made the New York Times bestsellers list. So I think that tells you something. There is an appetite for books about justice and that’s how I categorize true crime books – they are books about justice. And so I’m thinking I will probably do another one. I have found a case that is so interesting to me that it’s amazing no writer has already gotten to it. It’s another Michigan case, but I haven’t felt a need to go further afield than my native state because we’ve got plenty of interesting cases here to research. These historic true crime cases feel as immediate to me as if they are happening right now. Yes, all the people are dead but to me it still seems incredibly immediate and I hope that comes across to readers. If I am able to convey that immediacy even on a case that’s more than a hundred years old I feel like I did my job. Unfortunately it seems to take me longer and longer and longer until I finish the research and actually write the book and it’s published. I haven’t quite ever been able to shorten that time. So “Good Hart” took me a year and a half, “Isadore” took me two and a half years, and then “Wicked Takes the Witness Stand” took me six years. So hopefully this case is not going to take me any longer.

Open Mic: What is it that fascinates you so much about this particular genre?

Link: I think I have this need to try and assign logic to these illogical situations, I think it comes down to the whole “why” question. Why the crime happened in the first place. In order to answer that question you have to do this very painstaking chronology on who did what when, and then, hopefully, you will eventually come to at least answer that question ‘why’ well enough that its worth reading 1,2,3 or 400 pages to get to the answer. So I feel like I’m writing the book for me. The miracle of writing and publishing, what continues to amaze me, is that I can write a book for me because I want to know and then other people are interested in that story as well.

Open Mic: Let’s talk about your memoir. What was the mindset you took into that? Was that a difficult shift for you from true crime to memoir?

Link: It was extremely difficult. Just to use the word “I” gave me tremors because as you know, it’s drilled into us as reporters that you never use the word “I” unless you’re on the editorial page. I also had this idea of memoirs of being fluff and unimportant and unnecessary, and it hurts me to even say that now because I think there are some beautiful memoirs out there. But I was trying to create this career as a serious journalist. And while I was trying to do that I was writing these, I’m not sure if you’d call them journal entries or personal essays or just prose pieces about what it felt like to have the weight of the world on my shoulders and be raising these three sons in this rural lifestyle, this goal of keeping this rural lifestyle. And my whole plan was just to have these pieces that I could show my sons when I was older so I could say ‘See what our life was like? And we were able to live though that and this is what your childhood was, and look what heroes you were to your mom.’ That really was the goal of writing a lot of that early memoirist stuff. And then I entered one of those pieces in a contest and it won. So winning that contest changed the trajectory of my career. I thought, you know, maybe this is a book. It hadn’t occurred to me before that time. And I will tell you that many of those pieces, and definitely the one that won the contest, were rejected by my local coupon shopper. So the newspaper you get for free in your mailbox that gets covered with rain and mold before you throw it away, the editor of that publication that just needed something to run between the grocery store flyers, rejected that book. Then I entered it into a creative nonfiction magazine’s “anger and revenge contest” and I won first place. It was $1,000 prize money, and at that time that was like winning the lottery. And so I thought ‘maybe there’s some potential here.’ Winning that essay contest got me a literary agent and she said you know, “you’re not a true crime author, you’re a memoirist.” And I thought, ‘well this is a challenge, I’m going to see if I can do this.’ And it was a different kind of satisfaction, learning how to write about my own life, than the kind of satisfaction you get from some true crime work. I think maybe my career would be further along if I was willing to choose one over the other, but I enjoy them both.

Open Mic: Would you have handled the rejection from the coupon shopper differently had it come before you had the success with the true crime?

Link: Oh probably. I’m sure I would have just tucked tail and not sent them out anymore. But you know, I had had some success with the true crime books, though this was prior to Wicked, so I didn’t have a bestseller or anything like that. I wasn’t even making a living yet as I writer, I was just freelancing and editing other people’s work and taking side jobs and things like that. But I still knew what it felt like to be an author and to have a byline and so I wasn’t willing to have one editor’s rejection be the final word.

Open Mic: Rejection is such a huge part of this pursuit, no matter what genre you’re writing in. But how have you traditionally handled rejection, starting maybe from when you were younger and first getting into this to how maybe you look at it now?

Link: I attended a conference and there was a session where a visiting writer gave a whole program on rejection and what rejection means. Prior to that I was easily crushed by rejection, especially if I had something I thought fit perfectly with a particular editor or a particular publication. This writer said “rejection means one thing: it means you are sending out your work.” And I’ll never forget hearing that. It changed the whole way I thought about rejection. I started thinking of it as an acknowledgement. It is sending my work out, it’s not just writing it and letting it sit in a notebook or on my computer in a file folder. Or sit in a stamped envelope that I haven’t had the courage to put into the mailbox. All rejection means is that you are sending out your work. And that remains true because I’m still rejected by publications that have published my work before. You have to put gas in your car to drive to the library to do your library talk and you have to get rejected. That’s just the way it goes.

Me: When you’re in the midst of the bleak times that you have experienced and wrote about in Bootstrapper, did it ever really get close to where you said ‘I’m just going to go get a damn job and I’ll do my 9-5 or whatever and I’ll at least know I’ll have x amount of dollars coming in?’ For lack of a better term, taking the easier way out than to try and pursue this dream.

A Year in the Life

Link: If I knew what was coming, if I had the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, I think I probably would have done that. But I was always thinking we just needed to get through this month and then everything will be fine because I will sell a story or get another editing client or get a regular column. I always felt like what I was writing had merit and that I worked hard on it and that it was valuable and that someone was going to recognize that and that along with that recognition would come income. I don’t think I realized how long we were going to be without, and if I would have realized that I might have done things differently.

Open Mic: That’s really interesting because I think sometimes, again for lack of a better word, ignorance is our best friend.

Link: Yep, it protects us from ourselves in a certain way.

Open Mic: Tell me a little bit about process. How different was your process for true crime versus memoirs? Do you blend these things or are they very distinct for you?

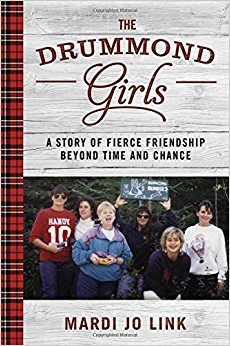

Link: I can only be working on one sort of writing at the same time. I just finished a personal essay that’s going to be in a collection that Wayne State University Press is publishing. I haven’t been able to do a lot of true crime research while I was working on the personal essay because it just uses a different part of the brain. So I really try and focus just on either the personal writing or the true crime reporting research. But I like to think I also use my research skills with the memoirs. With Bootstrapper I had photo albums, I had logs of what we spent on the garden and on the animals. I had divorce paperwork, I had my tax returns. For “The Drummond Girls,” the second memoir, I had books that my friends and I had kept. We all had our individual diaries and individual photo albums. I had a map. I had histories of Drummond Island. So with both projects I still have a lot of paper research that I do. The difference is that once I’ve done the research for the memoirs I pretty much put the paperwork aside and just write. Whereas with true crime you’re constantly going back to the paper documents. You’re constantly checking facts and looking for dates and things like that. When it’s your own life it’s not necessary, or at least I found it isn’t necessary to do that. With the true crime books I never question whether I should or shouldn’t put something in. I have a pretty good reporter’s instinct for what moves the story forward and whether it needs to go in or not. With memoir it’s a lot more difficult to know. Because you know what was exciting to you, you know what tied to emotion for you. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that it needs to be part of this narrative arc that you’re trying to build into your life. So that was a little bit more difficult for me and that’s where an editor was extremely helpful on what to keep in. For example, the first draft I turned in for Bootstrapper was very wide ranging, and I got an eight page single spaced letter back saying “the story is here, but there’s a lot of stuff you need to take out and from here on out I don’t want you off the property. Everything you write should take place on the property.” And those constraints were really helpful because it made me focus the story. Whereas with the true crime book, no editor is ever going to have to tell me that because I just have the instincts to know it on my own. With memoir it’s hard to be objective towards your own life and your own mistakes.

Open Mic: You’re very rooted to Northern Michigan. How has that impacted your work? You mentioned that geographic locations helped you choose some of your crime stories but how does it impact the rest of your work?

Link: I think you know in looking at both the memoir Bootstrapper and the The Drummond Girls, there is a work ethic, I don’t even know if that’s the right word, there’s a necessity of labor that runs through both of those books. So in Bootstrapper we did a lot of physical labor. My kids did chores. I don’t want to be the old women who says ‘in my day’ but I wonder how many kids do chores today. You know all three of my boys have had a lot of success, but not because they have any Harvard degrees or anything like that. They’re just good workers. So I think in Bootstrapper there’s a moment of pride in our work and pride in our accomplishments that we’ve gained through work. And then in The Drummond Girls the reason we went to that island and that was our vacation was because we were all waitresses and our money was precious to us and that’s all we could afford was to drive a few hours, take a ferry to some remote, rocky, woodsy island and bring our own sloppy joes on the way. So I think maybe that’s the thread that ties my writing life: the importance of physical labor and how you know some of us have moved, I think, too far away from that.

Memoir #2

Open Mic: The simplest thing I ever heard in my life about writing is that writers write. End of conversation. You don’t have to necessarily be super successful and have sold a million books, but if you’re not writing then you’re not a writer.

Link: Writers don’t just talk about writing. They don’t just dream up plots. They don’t just talk about the books that they’re reading. They don’t just talk about the sitcom pilot that would make such great TV. They actually create it. Writers are known procrastinators and I’m definitely guilty of that sin and yet whenever I’m up against a deadline I meet that deadline. I crank up the work. When I have something staring at me that I really don’t want to do, I usually just look at it and I think ‘it beats waitressing.’ I was a waitress for three years, I know. Any kind of writing, for me, beats waitressing and that is enough to make me make the deadline.

Open Mic: If you want to be a writer, you have to put words on your screen. If you’re not doing them…

Link: Right, if you’re not doing them you’re not a writer. I’ve had five books published and some of them have been really successful. One got optioned for a movie, and yet I still have to do things I don’t want to do. I still have to tackle sections of work that maybe are not my favorite. You still have to sit down and you still have to write that column. Sometimes when I sit down to write it might be due in three hours and I have no idea what I’m going to write about. And you still have to make it into something other people want to read. I guess is what I’m trying to say is it isn’t all waiting for the muse.

Open Mic: I’m glad you mentioned the movie option. It has been optioned by Rachel Weisz, correct? That had to be incredibly thrilling. What’s the status with that?

Link: First I want to tell you how it happened because it is just as quirky as how I got my first book contract. Here in Traverse City we have a really growing and pretty vital film festival every summer. It was started by Michael Moore but it has grown way beyond perhaps even what he envisioned. Last summer we had 160 films here. This whole town doesn’t even have 40,000 people in it and maybe a hundred thousand people showed up to our town to see these incredible movies from all over the world. So the summer that Bootstrapper was released, in May of 2013. a woman named Laurie Collyer had her movie “Sunlight Junior” here. She left the book she was reading on the airplane when she arrived in Traverse City, and she asked the driver hired by the film festival if there was a bookstore in town. He said “oh yeah, there’s a bookstore right next to your theatre.” And she said “great, could you just stop there?” So he stopped in front of Horizon Books, she walked in and Bootstrapper happened to be on the front table, she picked it up and read it that night in her hotel room and then she emailed her best friend and said “you know how we’ve been looking for a project to work on together, I think I found it.” And her best friend is Rachel Weisz.

Open Mic: You do have good karma.

Link: So maybe a couple months go by and I am in my car just getting ready to go into the grocery store and my cell phone rings, and it’s my agent and she said “do you know who Rachel Weisz is?” I said, “isn’t she an actress?” And she said “Yes, she’s the actress who wants to play you in the Bootstrapper movie.” And I said “what?!” So then she explained the whole story to me. Rachel and her attorney and a Hollywood co-agent worked with my agent. I was completely mystified by the process and just signed the paperwork. That was in 2013 and they’ve since renewed it a couple of times. Rachel has talked about it in an article that was in The Globe and Mail, and they’re renewing it again, so it could actually happen. That is a very bizarre concept to me. But it would be terrific. I’m a big fan of her work. I think she’s a terrific actress and it would be incredible if they said one single mother’s life in the Midwest is worthy of the cinematic treatment. You know that would be pretty thrilling to me. I’m not really holding my breath because an awful lot of books get options and very few movies actually get made, but I’m hopeful. In the meantime it’s a little bit of money. I mean it’s a lot of money if they actually make the movie, but its money that you didn’t do any additional work for and it allows you time to write. That’s kind of how I think of it.

Open Mic: I’ll end with a question I like to throw at people every once in a while. If I had the power to give you the opportunity to have dinner and a conversation with any one of the following three people, which one would you choose? You’re from Michigan so I’ll offer up Detroit Tigers great Ty Cobb, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder and legendary film actress Katherine Hepburn. Which of those people would you be most interested in sitting down with?

Link: I would have reasons for all three. My dad was a college baseball player and I’m a huge sports fan so I would have a lot to talk to Mr. Cobb about. I’m a big fan of Katherine Hepburn’s work and I think that conversation would probably be the most interesting. However, the one that would be the most…let’s use the word effective…I would have some things to say to Mr. Snyder. It might not be an actual conversation – it might be a lecture – but I would choose Mr. Snyder.