Sacramento Bee columnist Dan Walters

Sacramento Bee political columnist Dan Walters has been a newspaper guy for more than five decades. He has exclusively covered the machinations of the California Capitol since 1975, giving him a front row seat to some of the most colorful and important political figures in state history. That history also happens to be one of his enduring interests, and something that regularly works its way into his must-read columns. He has also written or co-written three books on dealing with California’s political and social evolution. I sat down with him recently to talk about journalism, writing and how much you can learn about California by reading good noir fiction writers like Dashiell Hammett and Walter Mosley.

RE: You’ve been writing your column for how many years now?

Walters: I’ve been writing it for 35 years, last month.

RE: And reporting for how long total?

Walters: I’ve been in the business for 56 years in September.

RE: Where did you start?

Walters: At the Humboldt Times in Eureka, California. Started as a copy boy the day after Labor Day in 1960. The first person I met when I walked into the room for the first day was Estelle Goodman, who is now Estelle Saltzman here in Sacramento. She was from Eureka, her father is a doctor up there, and she had a summer internship and was on her last week before heading back to college. She was the first person I physically met on the first day I showed up for work. I was 16 years old, about a month shy of my 17th birthday.

RE: The industry has changed so much over the years. What’s your perspective on where we’re at right now in journalism?

Walters: I really think it’s better than it ever has been. If you look back on journalism over that span of the last century-plus, it’s evolved from a kind of jumped up blue collar trade into at least a quasi-profession, and I think the standards have become better. With newspapers the coverage, as well as the editorial page, would always reflect the prejudices of the owners and I don’t think that’s tolerable anymore. Although newspaper competition has declined, I don’t think journalistic competition has declined, and I think it reflects that. And maybe that’s because newspapers have become a hungrier business. It’s become more aggressive in really trying to find that niche they fit into, particularly the watchdog niche. I think the quality of journalism is much better than it was 50 years ago.

RE: What about the social media influence, especially with we’ve seen so much of the “first before correct” mentality?

Walters: We’ve seen some mistakes, but given the volume of what goes on it’s amazing there aren’t more. You have to look at journalism now as multilayered. The first layer is something like Twitter -140 characters and just get it out there. The second layer is the blogs, like our Capitol Alert, where the motto is, ‘get it up there as fast as you can but still within the standards of publication.’ That’s not just something that will only be online. It’s going to be shown in the permanent record of the paper, though not all of it will show up there. Typically we might do four, five, six, seven items for Capitol Alert every day in the Sacramento Bee, but maybe only one or two of those will show up in the paper. And then you have the paper itself. So you have several layers of reportage, which is certainly a new wrinkle. At one time there was one layer. You wrote the story for the paper, and it didn’t particularly matter when you wrote it as long as you wrote it before deadline. Now it’s become much more time conscious. Twitter first, blog second and then maybe another version of it for the print media.

RE: Is that good or bad?

Walters: In a way I think it’s good because it keeps people on their toes. You can’t be lazy and say, ‘well I’ve got five hours until deadline, there’s no hurry to do any of this stuff.’ You can take that attitude, but if you know that whoever you view as your competition is going to try to get that thing out online before you do, that’s a whole different story. The motto of the Bee these days is get up what you can verify as fast as possible and fill in the blanks later as you get more verifiable information. And then the final product, if it’s important enough, goes into the printed paper. The other thing is you don’t have space limitations electronically, so you can kind of roll with more than if you have to fit everything in a limited space. When I started the business, we were still using technology that hadn’t changed since probably the late 19th century. Now it’s all electronic. Eventually the actual paper will disappear. It’s inevitable. I think it’s only a question of when. Younger readers are not interested in print papers and eventually it will evolve, which doesn’t particularly bother me.

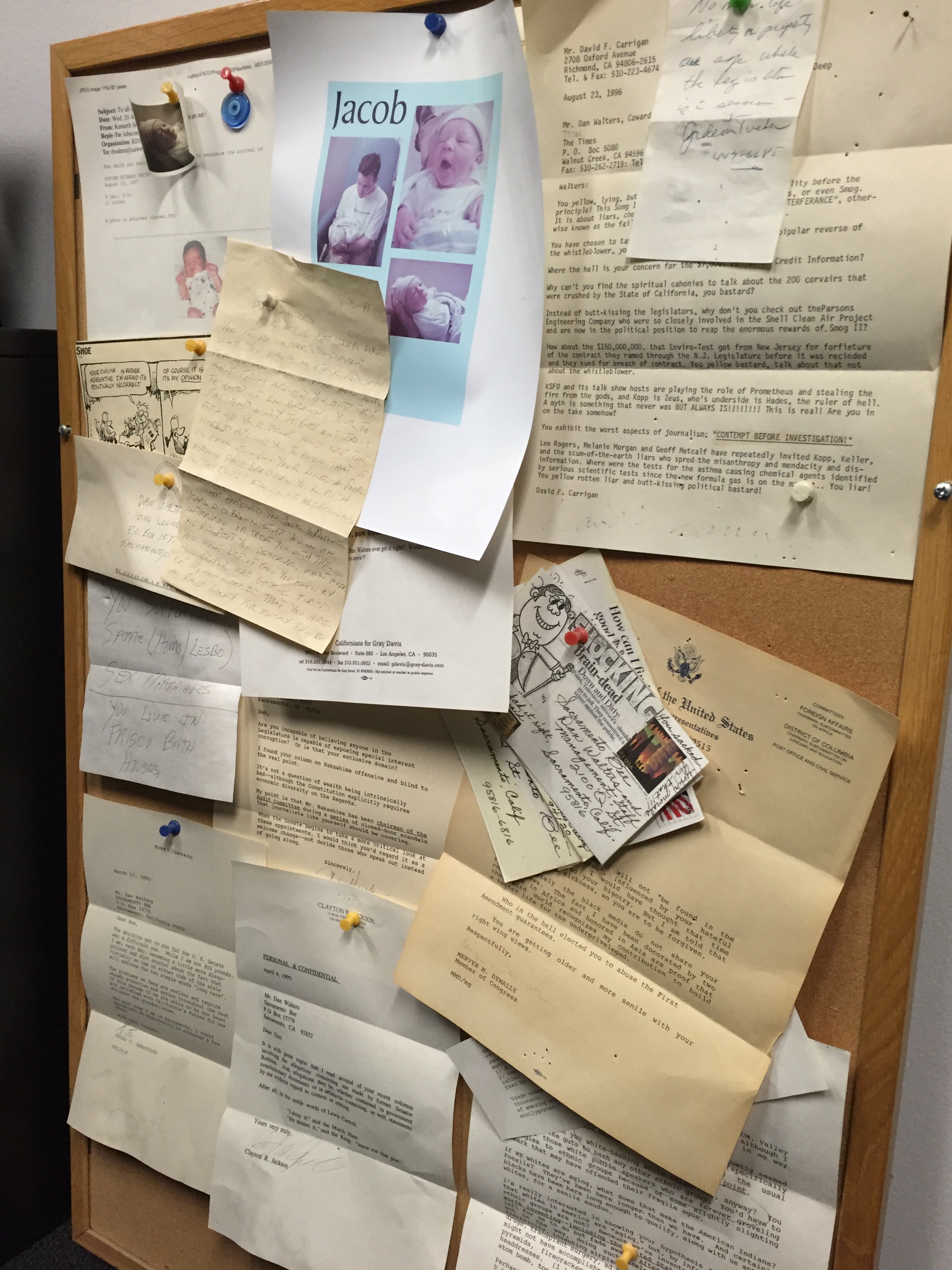

Every columnist gets hate mail. Not everyone has a collection from some of California’s power elites.

RE: We hear constantly about the decline and death of newspapers. Sounds like you don’t buy it.

Walters: Well, the print newspaper will decline and die. There’s no question about it. As electronic reading devices become more common and better and more portable and all this other stuff, the print paper will die. But that doesn’t really bother me. My attitude toward journalism, particularly political journalism, is there is an appetite and market for it. The only question is how you transmit it and make money. The trickiest matter of the whole thing is making money. Newspapers clearly made a big mistake in giving content away back in the 90s and 2000s. They got panicky about the electronic revolution. They should have established a system of paying then, because once people got used to getting it for free it’s very difficult to charge them for it. At the same time, however, you cannot continue to give it for free, because doing the job costs money. You have to figure it out. Obviously the Googles of the world have figured out how to make money with online stuff. And we are slowly but surely doing that. The McClatchy newspaper gets a substantially large portion of its income now from online advertising. That’s number one. The other thing you have to remember is if you eliminate the print paper you eliminate a tremendous amount of cost. Cost of printing, paper, ink, all those trucks that deliver the paper, and all that manpower that takes to deliver the paper to the front door. All that goes away. It’s probably a third of the cost structure. Once that goes away, you could make money on a much lower revenue base than you need for print paper.

RE: Would that, in your opinion, improve reporting in that you would have more resources to pursue stories that sometimes become resource-prohibitive now?

Walters: In an ideal world that would happen. At the very least it means there’s a crossover point at which your online revenues get to a point that you can have a successful operation all online. Then the print paper becomes a money loser. And there may be interim steps along the way, things like three times a week publication of the print paper. We know there are certain days that are more profitable that others and have higher readership than others. Probably Wednesday, Friday, Sunday would take care of the needs of 80 percent of your readers 80 percent of the time. So you could conceive of that. The problem is you have to maintain the infrastructure even if you’re only publishing three times a week. The real economy of scale comes if it goes away altogether.

RE: What about aggregators?

Walter: At some point the aggregators will finally have to start ponying up if they want the material. If you go on any aggregation site now, a lot of what you want to read is behind a pay wall, and those pay walls are getting tighter and tighter. You get 10 free stories a month and then it’s going to be seven and then it’s going to be four and finally it’s going to be nothing. If you want to read, you’re going to have to pay for it. Either the reader is going to have to pay for it, or the advertiser will. In classic newspaper economics, the subscription page is only about a quarter of the cost, and about three quarters of it comes from advertising. It’s different in Europe, where they have relatively little advertising and readers pay a much larger share. And it’s obviously different ton websites that are free to access, like Google. But the material they’re steering you to is very often behind a pay wall. So that whole thing is sorting itself out. I’m kind of a spectator to all of this. It’s my hobby.

RE: Hobby?

Walters: [Laughs] All of us old farts have to have a hobby. I could have retired a long time ago but I like doing it. I’m a spectator who likes dabbling in newspaper stocks. So I’m interested in it but my life isn’t going to be affected by it. That puts me a different situation than most. I see the struggle going on. How do you make that transition, how do you make money in that transition, how do you have the wherewithal to do the journalism that gets the readership that drives the ads? Which has always be the newspaper’s problem. Now it’s just in a different arena, electronic rather than paper. I think it’ll happen. I think underlying the whole thing is there is a market and a demand.

RE: People ask me all the time, would you recommend this field to young people? What do you think?

Walters: I think the skill set has changed. It’s become more complex. Now we hire reporters who know how to do video. But the reporting skills haven’t changed. There’s always going to be a market for reporting. Journalism is a filter. It’s taking a wide array of events and distilling them down to some sort of understandable digest. Even the lengthy article in a newspaper is still a digest of some kind. It’s taking a whole bunch of stuff and compressing it into something that can be easily digested. There’s always going to be a market for that because you simply can’t keep up with what is going that is of interest and important to you without it. It’s impossible.

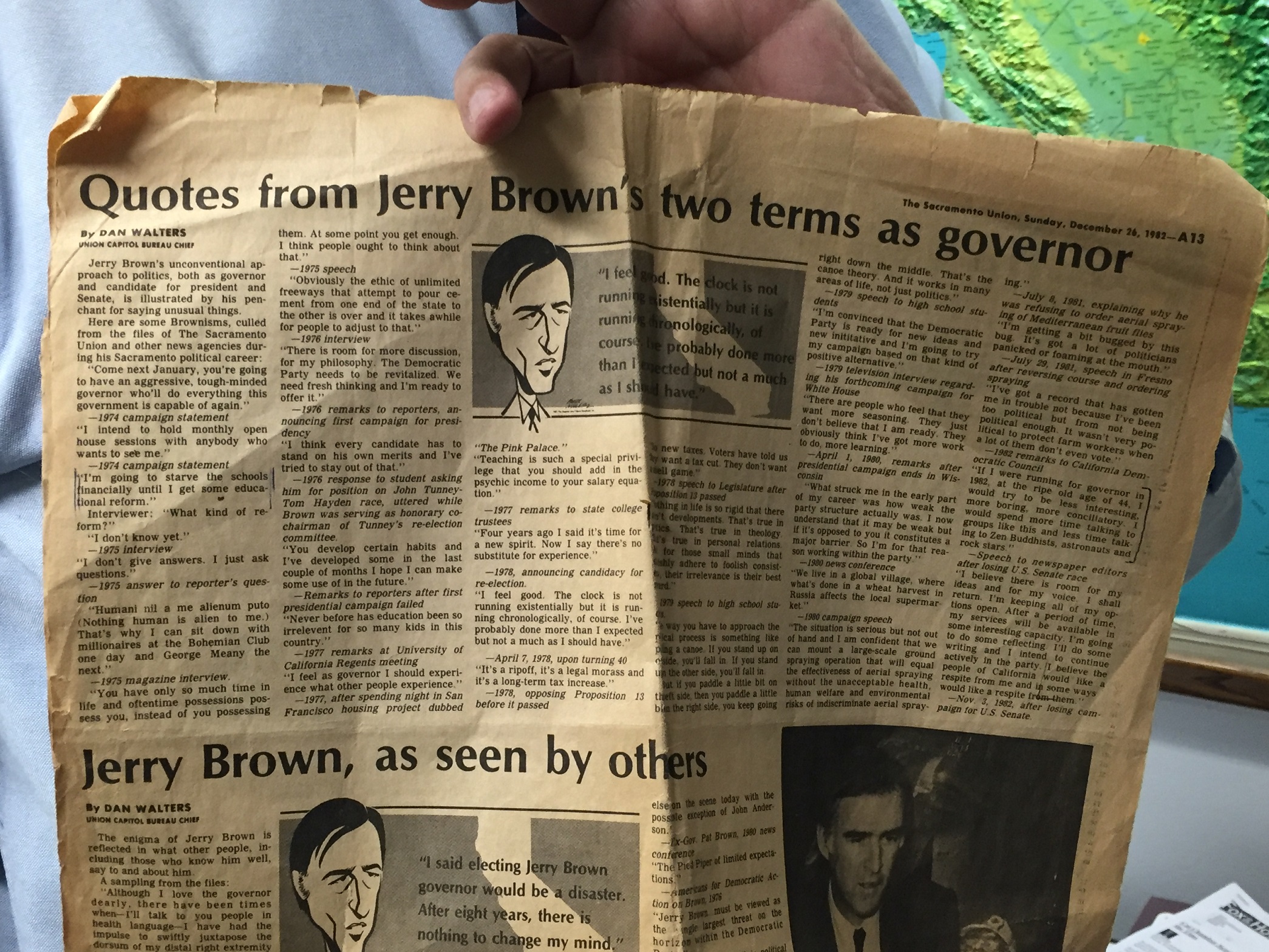

The headline says it all

RE: People read your column for the insight of what’s happening in government. You’ve covered many politicians. Is Jerry Brown the most compelling political figure you’ve covered? Who else comes to mind?

Walters: I think Jerry Brown is the most compelling. Arnold [Schwarzenegger] was interesting. There have been some other characters who have been interesting, but Jerry is compelling simply because of the unusual nature of being governor at such a young age, being gone for 28 years and coming back in the role of the elderly person being governor again. Watching him in the context of having watched him before, in the pre-electronic age, is compelling to me. That is the Jerry Brown archive, right there [pointing to a box of newspaper clippings, photos, etc]. When Jerry Brown left the governorship, I wrote quite a few things for Sacramento Union, one of which was a distillation of all of his best quotes from his first governorship. And then all the observations that were made about him by others, and a long review comparing Brown and Reagan. But this quote thing, it’s priceless. You can’t find this anywhere else. I took everything that had happened in eight years, all the pithiest things he said, and I still refer to it once in a while.

RE: You once had an unusual encounter with baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams. How did that happen?

Walters: I was 16 years old, and I’d been in this business about two weeks. It was late September of 1960. I was usually the first person in the newsroom at 3 o’clock, and the phone rang, and it was the people at a local seafood restaurant in Eureka. They said, ‘hey Ted Williams is here.’ So I grab the photographer and went down there. I kind of knew who he was, but I wasn’t a big baseball person. And there was Ted Williams sitting with a very attractive blond woman at this restaurant, Lazio’s. I didn’t know was Ted Williams hated reporters. But he recognized the situation better than I did. He was a well-known womanizer, and the situation was, ‘oops, I’m here with a woman not my wife and here’s a guy with a camera.’ He recognized the peril and he quickly offered me a deal. He would answer a few questions, take his picture, but leave her out of it. Which I, in my naiveté, did. So that’s how I ended up interviewing Ted Williams, two weeks into it at 16. Fast forward to three or four or five years ago. There was a big documentary on him on public TV or some place, and I was watching with my wife and I told her the story. Then it showed him with his various wives. The last wife was the blonde woman I saw. I didn’t know that until I saw this documentary that she was the last of the Mohicans. [Laughs]

RE: Who are some of the other compelling figures?

Walters: Sir Edmund Hillary. It was in Eureka. I had graduated from copyboy ranks by then and was a reporter. He came up there with some people from National Geographic to tout the idea of creating Redwood National Park, so I interviewed him. And Richard Nixon, when he was running for governor in 1952. Interesting stuff. I once talked to John Glenn about whether we were related or not. He’s from Ohio, and my mother’s family from Ohio are Glenns. We decided we probably were. I’ve since done a lot of genealogical research and found out that are not related, at least in America. Maybe back in Ireland it’s possible. But in doing that I found that I do have a relation with a man by the name of Hugh Glenn [for whom Glenn County is named], who was a 49er and, to make a very long story short, became the largest farmer in California. He invented agro-business in California. In the 1860s and 70s, he was farming 50,000 acres of wheat land up in the Sacramento Valley and was known as the wheat king of California. He was the 1879 Democratic candidate for governor. He lost. He was up there at the same time as Jerry Brown’s ancestors. Undoubtedly they knew each other, although Brown’s family hadn’t come until 1852. I told Jerry once that his people were considered newbies.

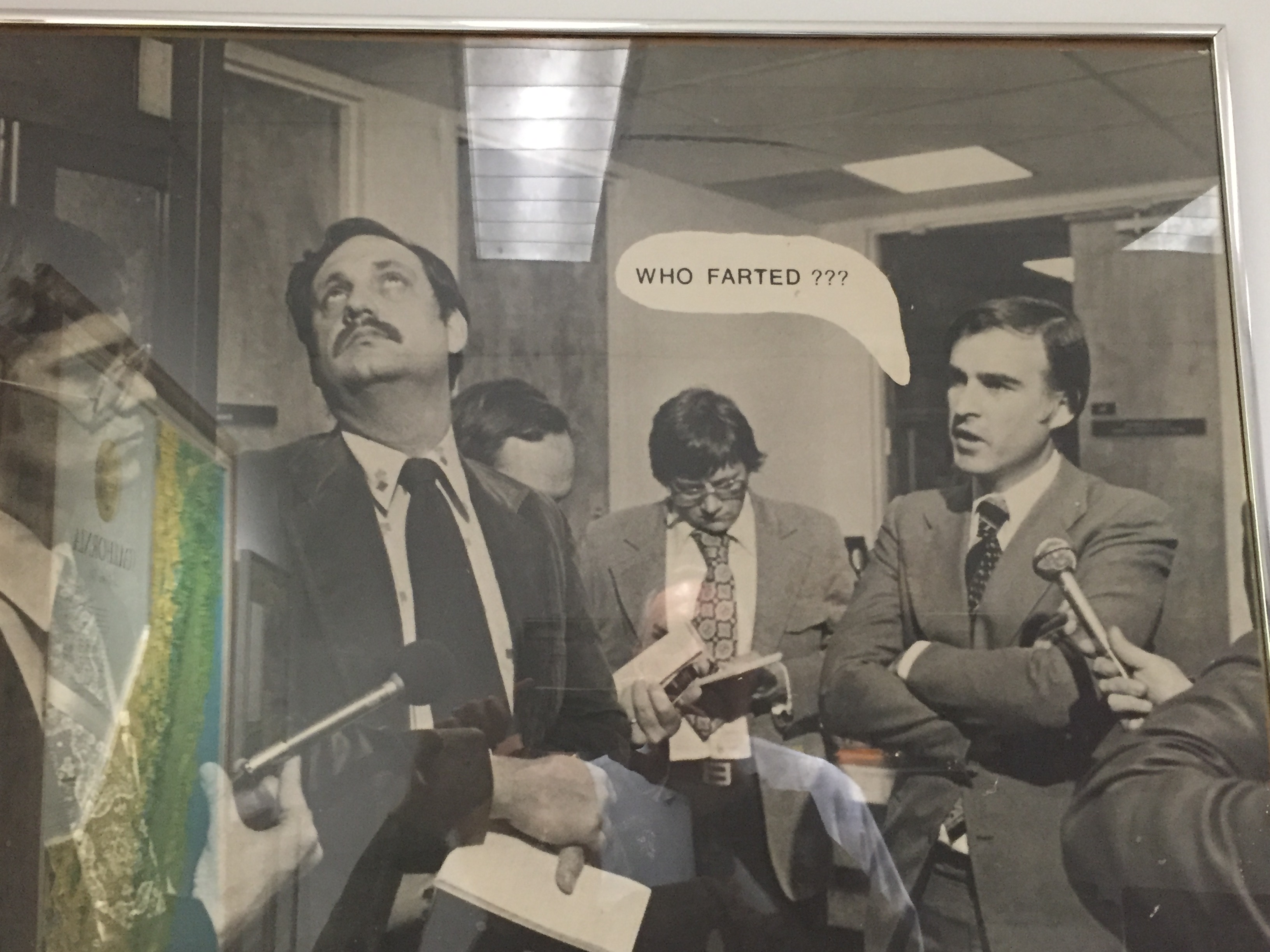

A caption contest winner hanging on Dan’s office wall

RE: Your book “The Third House” explains lobbying as well as anything I’ve seen. With all of your experience, why are you not writing a book a year about all of these other things?

Walters: Because I’m lazy. Because I write a column every day. What I try to do though is bring a sense of history into the thing. So if you’re interested in the development of agriculture in California and how it has evolved as the largest agriculture producer in the United States, you have to go back and look at people like Hugh Glenn who basically invented large scale, mechanized, heavily capitalized, export-minded agriculture that now dominates California. These are not little family farms in California, for the most part. They’re big operations, and that’s where it got started.

RE: Then why not do a book of this compelling agribusiness pioneer of California?

Walters: I always said that if I ever wrote another book I would write about California politics. I would call it “Unintended Consequences” and it would be about all the great schemes that are enacted by lawmakers that backfire. But I haven’t done it. Though I’ve written a long article about these unintended consequences, which will run in the Bee in the near future.

RE: One of the compelling things that separates your work from others who cover California politics is that steady stream of connectivity to our history.

Walters: I do think one advantage of writing a column over writing stories or articles is you can put that in the context of what’s going on. I also like data. I think there’s a lot of truth in data that kind of gets lost in the ‘he said, she said’ atmosphere of journalism. What is the real data about that? What are the real numbers, whether it’s poverty or unemployment or anything, taxes, spending? We cover the budget and lawmakers want this and that, but what is the real data? How much is it going to cost? Where’s the money going to come from? So I try to work as much data into my column as possible. And not only data of the moment, but historic data. The column in today’s paper starts out with the fact that the state has borrowed $45 billion over the years to build schools. And now there’s this conflict over bonds and whether there is going to be another school bond or a mini bond. So I do like to throw some data into these things so it frames it in more objective terms.

RE: You’ve said you can follow California’s 20th century evolution through its great writers. Tell me more.

Walters: In the process of writing their stories, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler and Ross McDonald and Walter Mosley and all those who have come since have imparted a sense of the time and place they were writing in. Mosley is interesting because he writes of an era that’s preceding his own. He’ll go back to WWII essentially and describe how blacks came from the south to Los Angeles to work in the war industry, because all the men were being drafted otherwise. And then the white men came back from the war to claim their jobs in these industrial plants that were downsizing because of the end of the war and you left behind a residual black community without any real economic underpinnings. That’s very clear in Mosely’s book as he follows his main character from the end of WWII forward. And the same thing is true of the others. If you read Hammet’s The Maltese Falcon, you get a very good sense of what San Francisco was like. They still do tours over in San Francisco showing all the places that are mentioned in The Maltese Falcon, for example. I think Raymond Chandler had a really good sense of time and place in Los Angeles in the 30s and 40s. It was a place that was undergoing a lot of pretty incredible change at the time because of the war. And you do have a sense of place if you read his novels. Same thing with Ross McDonald. Him probably most of all because he consciously reflected various aspects of California society in his books in the guise of his private detective stories. I can’t remember how many that we’re made into movies. There was a well-known one starring Paul Newman called Harper. The character was called Lou Archer but they changed the name to Harper in the movie. He set his books primarily in a placed called Santa Teresa, but it was really Santa Barbara. But they weren’t all confined to Santa Teresa, so you got a sense of things like farm labor conflicts and other things going on in Los Angeles at the time. Or the oil industry, which was very prominent in Santa Barbara. You could do worse than reading Hammett, Chandler, McDonald, Mosley and Michael Connelly in chronological order. Then you’d get a pretty good idea of how California evolved over time.

Dan Walters has been covering California politics for the Sacramento Bee since 1984. His columns appear in the Bee and dozens of other California newspapers several times a week.