Writers are often told to write what they know. For someone who has spent as much time living and working and getting into mischief around the globe as Timothy Jay Smith, that could only mean writing award-winning thrillers and screenplays based in exotic locales. I sat down with him recently to discuss his new novel, “The Fourth Courier,” the publishing landscape for books with gay characters, and how writing screenplays makes him a better novelist.

Writers are often told to write what they know. For someone who has spent as much time living and working and getting into mischief around the globe as Timothy Jay Smith, that could only mean writing award-winning thrillers and screenplays based in exotic locales. I sat down with him recently to discuss his new novel, “The Fourth Courier,” the publishing landscape for books with gay characters, and how writing screenplays makes him a better novelist.

Open Mic: We’ll talk about process in a bit, but right now tell me a bit about “The Fourth Courier.”

Smith: The timing of the book is the spring of 1992, about three to four months right after the fall of the Soviet Union, which was dismantled legally on Christmas Day 1991. That is an important thing to note because that’s when the border between Russia and Poland became very porous and there was a lot of fear that Russia was unable to really handle or secure all the nuclear material that it had. The story is basically that there has been a series of gruesome murders in Warsaw, Poland in the spring of 1992. On the hands of the third victim they discover traces of radiation. Because all three men had been murdered in the same way, the theory becomes that the couriers carry nuclear product out of Russia into Poland to go on to some place in the world. the US sends an FBI agent to work with the Polish police in order to investigate the case and try to figure out what’s really going on.

Open Mic: This had some basis in reality for you, correct?

Smith: Yes. I was on an assignment around that time in Latvia, where I had a meeting with a decommissioned and very unhappy Russian general who at the end of the meeting suggested we go somewhere where no one could hear us. He took me way out into this forest, I had no idea what was going on, and he said he could get me anything I wanted. I looked very puzzled at him and said ‘I don’t know what you mean.’ He said, “atomic.” There had been some discussion in our meeting about Russia’s nuclear arsenal in Latvia, and he apparently had some control over it so I think he had totally misunderstood why I was there and thought this was something he might be able to sell and do well with. I don’t know exactly what was in mind because I said ‘no, you’re totally misreading my purposes of being here.’ In fact, I was there to design a Peace Corps program for volunteers so I wasn’t there for nuclear materials. Some years later when I decided to become a full-time writer, this was one of the first stories I wanted to write about. I wanted to talk about the transformation from a communist colony situation to an open market economy. I wasn’t so much worried about nuclear material being smuggled out, but really trying to portray that moment in time and in Polish history, which was a hugely important time both for them and for the world.

Open Mic: You’ve lived a very interesting life. Have you ever considered writing a biography?

Open Mic: You’ve lived a very interesting life. Have you ever considered writing a biography?

Smith: I am not particularly interested in sitting down and doing a straight autobiography of ‘I was born in 1950 and here I am 68 years old and what I’ve done in my life.’ All my books are probably autobiographical. “Cooper’s Promise,” for example, has many things that came straight out of my life.

Open Mic: Is that in some ways more liberating for you as a writer and as a storyteller than doing sitting down as you say and just writing a straight kind of linear biography would be?

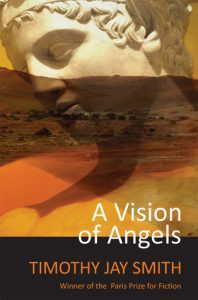

Smith: Well, one thing that motivates me both in terms of my writing and in terms of the career I choose earlier in my life is really focusing on social justice. “Cooper’s Promise” is about human trafficking and blood diamonds. My very first novel, “A Vision of Angels,” deals with the Israeli/Palestinian conflict because I also lived there for two and half years and I saw that conflict from varied perspectives. That’s really when I quit working to write the story that I wrote, which allows me to view that conflict with four different perspectives: an American journalist, a Palestinian farmer, an Israeli war hero, and an Arab Christian grocer. My feeling after I had worked there for a couple of years was that the situation is never going to get resolved unless everybody has a place at the table and unless we try and understand everybody’s perspectives. What I do is I take thriller plots and look at them from the perspective of who is really being affected by a fact or an incident. In “Cooper’s Promise” it’s a young girl who has been trafficked, but I’ve got a couple of other books in the works where I do the same thing. I don’t think I could do that through an autobiography. If I fictionalize it and show how these things affect ordinary people, it’s a lot more effective.

Open Mic: You also write screenplays, something I think a lot of writers aspire to. Do you have any advice for aspiring screenwriters?

Smith: Learn how to write a screenplay. Take some courses because it’s a very different form of art. I decided to write one as I was finishing up “A Vision of Angels,” my first novel. I was taking a short course with Sebastian Junger, who wrote “The Perfect Storm,” and he said he had just sold the film rights. I asked if he was going to write the screenplay, and he said he had nothing to do with it and that’s just how the business was. I thought that may be how the business is, but if I had spent three years putting my heart and soul into a book, I would want to know at least enough about the screenwriting process and techniques to have some artistic input into that process. After that, I took a couple of screenwriting courses and really fell in love with the format. I think it’s a lot of fun to write them. Every novel I’ve written – I have four complete novels now, and this is the third being published – the screenplay is my last editing tool. By writing the screenplay, I am forced to think about the book’s most important, dramatic through-story. You can’t go off on a lot of tangents or backstory in a screenplay because you don’t have that much room for it. You have 120 pages, that’s it. It’s also very good for writing or sharpening dialogue, and that’s a good editing tool for me as well. I think it’s a really worthwhile thing as a novelist to also be able to do a screenplay.

Open Mic: You’ve noted that there are still very few thrillers and mysteries which feature gay characters. How would you describe the publishing landscape right now for gay authors or genre fiction featuring gay characters?

Open Mic: You’ve noted that there are still very few thrillers and mysteries which feature gay characters. How would you describe the publishing landscape right now for gay authors or genre fiction featuring gay characters?

Smith: I think it’s a very positive place to be right now. When I first started writing, and I’ve been writing for 20 years now, friends said not to put myself out there as a gay writer. They said I would get pigeonholed, that it wouldn’t be good for my career and I wouldn’t be taken seriously. The idea of a gay writer or a gay book, people just thought it was all about sex and sex and sex. But I’m a gay man, so it seemed odd to me. Why wouldn’t I write about gay characters? I write about characters that reflect me, because in a lot of ways that’s just what happens as a writer. But the feedback I have gotten has been very positive. Nobody has said, “Oh God, not another gay book.” This is great because thrillers are a genre where gay characters don’t really exist, and people have welcomed it. It’s never come up with my publisher or my publicists, but the fact that I want to promote it as a gay book or gay literature has really turned my publicist around to understand that there is a huge market out there. They weren’t going to push that, so I pushed them to say this is the market that we ought to be going after and I think it’s really going to pay off. The fact that Bookstr, which has 1.57 million followers on its webpage, selected The Fourth Courier as one of five novels this year to honor the Stonewall anniversary, I think is going to give me a big push in the market.

Open Mic: Most writers have a wealth of plots and characters stored away in their head. Which do you usually start with – plot or characters? Which matters more to you?

Smith: I basically start with a notion of what I want to write about. For instance, I did a lot work with refugees coming into Greece from Turkey in 2015 and 2016. I wanted to write something about the refugees, but I only knew what happened when they came to Greece. I didn’t know what happened to them while they were in Turkey, so I started to research that. I had to find my character, and by the time I thought that through I had a sense of what kind of story this is going to be. I have a sense of an opening scene, and I have a sense of a closing scene. Then I basically brainstorm on how to get from the opening scene to the closing scene. I start filling in an outline and then I start writing. I keep a notebook right next to me as I write where I keep the dialogue that I know I’m going to use somewhere down the road as well as my character’s backstory and how far am I going to go back on that and how do I pull that in to the dramatic current story. I use it to think through all that.

Open Mic: What makes a great thriller for you as a reader?

Smith: I write the kind of books that I like to read and those books are fairly fast-paced. I like something fast-paced when it’s really about the people and not only about the action. I really like something that’s more fast paced, but it’s really about the people and not so much about the action. I want to understand what has happened to people while they’re going through an event or situation. That’s why some people refer to my work as literary thrillers. The thriller is usually more action oriented and literature is usually more character driven, but I try to combine the two.

Open Mic: Thinking of format – do you prefer to write stories told from multiple perspectives or to stay inside the head of only one or two major characters?

Open Mic: Thinking of format – do you prefer to write stories told from multiple perspectives or to stay inside the head of only one or two major characters?

Smith: What I have written so far has generally been from multiple perspectives, but I recently discovered the concept of an open mystery versus a closed mystery. In the open mystery, either the reader or the audience actually knows more than the main character. We in the audience know that there is a bogeyman in the next room, but the protagonist doesn’t know that until he walks into that room. If it’s a closed mystery, we only know what the main character knows because the story is told entirely from one perspective. In the screenwriting world, Chinatown is an example of the closed mystery. Jack Nicholson is in every scene. “Cooper’s Promise” is also a closed mystery. Cooper is in every scene and there is not anything in that book that is not told to the reader through his perspective. The book I am now embarking on now, which is a story of a Syrian refugee in Istanbul, again told entirely from his perspective and not any other characters. And I like that. It’s a real challenge. I think that one of the problems of hopping around too much is that you don’t necessarily get a lot of depth in a character. Too many characters also confuse a reader unless you can really nail them early on. Those are two problems I was criticized for in my writing, that there were too many characters and readers I couldn’t follow them all.

Open Mic: We are a world now of instant gratification and short attention spans. Does this at all play into how you write your stories? If so, how?

Smith: I’m conscious of it, I’m aware of it obviously but I think that I’m part of that too. When I write I usually don’t write a 20-30 page chapter, it’s usually ten pages or something like that because that keeps it moving and it keeps my attention as well when I’m writing. I think my stuff is well received because it does appeal to people who want the faster, shorter scenes or stories, but there is also some depth to the characters and the dialogue so they’ll stay with me a little bit longer. But I don’t think you could write something like “The Magic Mountain” today.

Open Mic: The publishing industry has changed a lot in the last 20 years. Do you think things are better or worse now for writers than they were then?

Smith: I think they’re very different. Things are probably worse if your goal – which is my goal – is to become an accomplished, recognized writer with a traditional publisher. That’s what I really want in writing. I think that it’s gotten very competitive out there and there is a lot more junk being produced because there are no gatekeepers for self-publishing houses. It’s a lot more competitive, and the fact is that being able to put it in a PDF and sending it off in ten seconds creates a mountain of material that didn’t exist before, often unedited. So I don’t think these are the golden days for writers. I think people try to pretend they are because everybody can be published, but I have a slightly different goal.

You used to send your book off to your agent and they would manage it for you. They did all the publicity and all the promotion, but you can’t do that now, even with the Big 5. You’re now expected to go out and hire your own publicist. You don’t just sit in your office and write the next great novel. You also have to contact a thousand bloggers and try and get them to do an article on you. You’ve got to be part of the promotion. You have to be very entrepreneurial. Just last week I had a blog tour in the UK, and I’ve got something lined up in India as well. Those are opportunities that the writer has to take because you can’t really afford a publicist to do everything for you unless you are really, really rich.

Open Mic: I like to end on what I hope is a fun question. Let’s imagine I have the power to put you together for dinner and a conversation with any one of the following three people. Who would you choose and why? Your options are the late, great musician David Bowie, the lawyer and humanitarian Raphael Lemkin, or the FBI’s J. Edgar Hoover.

Smith: I would pick J. Edgar Hoover because I would like to know more about the FBI. When I was doing early research on “The Fourth Courier,” I got in contact with the FBI – those were the days when you could have some access to people – and I did a private tour of one of the FBI training camps in Quantico. I would be very interested in talking off the record to J. Edgar Hoover about the FBI and his homosexuality. I would be very interested in how you can do some of the things he did when that’s who you are yourself.