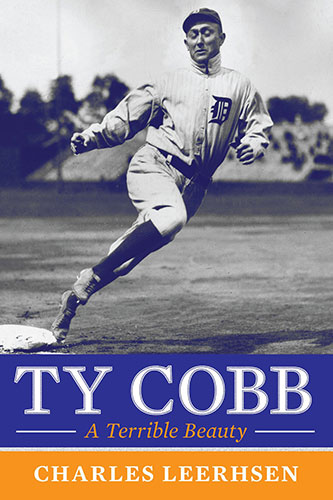

Like most baseball fans, I grew up believing the immortal Ty Cobb of the Detroit Tigers was one miserable, awful SOB. But thanks to the impeccable Charles Leerhsen I don’t believe that anymore, nor should anyone else. Those who stubbornly cling to that myth really should read Leerhsen’s fantastic book “Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty,” one of the most well researched, well written nonfiction books ever written on a sports figure. I sat down a while back with Leerhsen, a former editor at Sports Illustrated and the author of two other sports-themed books, to talk about Cobb, the need to let facts guide the story and his connection to a certain denizen of the White House with a bad reputation of his own.

Open Mic: I’m huge baseball fan. I’ve also been fascinated by Ty Cobb for most of my life, but until I read your book I had absorbed a lot of the mythology of what a monster he was. I grew up believing that and so this book was such a great revelation to me. What drew you to this kind of an examination of Ty Cobb?

Leerhsen: I’m not really a baseball writer, and I’m not really even a die hard sports fan. I’m a sports fan from afar at this point in my life and career. But I am fascinated by the era around the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I’d written two books before this one, one called Crazy Good about a race horse named Dan Patch that was the biggest celebrity in America in his day but which by then was almost completely forgotten. After that I wrote a book called Blood and Smoke about the first Indianapolis 500 in 1911, and I found that both horse racing and auto racing were a pretty hard sell in the marketplace. As big as the Indy 500 is, racing fans are not readers and vice versa. So the books did just okay. My editor at the time at Simon and Schuster said “why don’t we try baseball and open a new audience?” So I guess it was a commercial decision. So I go to baseball and ask myself who do people want to read about and who has not been overdone? I decided on Ty Cobb.

The immortal Ty Cobb doing what he did best

Open Mic: But why Cobb over someone else?

Leerhsen: Like you I had grown up with the myths. I thought he was a colorful character, this monstrous human being. I’m pretty good reporter and I figured I would find new and fresh examples and collect all the stories out there of him being a monster and I’d write this book and it would be better than another baseball player mostly because he was such a monster. Well, I spent four years on the book but it was probably within about 10 minutes that I saw that there was a problem with my assumptions. Practically the very first thing I found was a story about him backstage of a theatre in Atlanta in 1911. It’s the story from the opening of the book, and in that I saw this human being, a guy who was being courteous to other people and who was worried about pleasing the audience in this play he was in during the off season. Those are simple human things that seem unremarkable, but they didn’t fit the scenario that I knew of Ty Cobb. I should have known – and anyone that believed those stories – should have known that it couldn’t really have been that way. The Ty Cobb of myth is like a cartoon character like Wile E. Coyote or Daffy Duck. He’s always in the same mood when we check in on him, and you know no human being is like that. A guy named Timothy Gay wrote a book about Tris Speaker and he said that Ty Cobb was so crazed that if he walked down the street and saw a black person he would pistol whip that person. You have to know that the idea of walking down the street in these big cities and pistol whipping every black person he saw on the sidewalk can’t be true. I mean, he would have met his match or at least been detained by the authorities a few times, even though as a white man he probably would have had an advantage. But it just didn’t make sense and I should have known that. So I began to see the cracks. I began to see that I was going to have to tell a different story. It’s very hard to write a book, as you know, but it’s even harder to write a dishonest book in the sense that you’re trying to force someone into a certain scenario. I had to go where the evidence took me, like you would do in any story. I think and I hope that I wound up with a Ty Cobb who was a human being that’s a lot more interesting than the one dimensional character of myth. He was not a saint because no one is. He was somebody who sometimes behaved admirably and sometimes didn’t.

Open Mic: I actually had the same thought when I finished the book. The Cobb of accepted history really was a cartoon character. And it probably does stand to reason that we should have been questioning that myth for a long time, and yet until your book nobody really has. In fact, there was not only acceptance of this kind of mythology, writers like Al Stump actually took it and ran with it instead of doing what a real reporter should do. Did you ever find yourself asking how did nobody else ever report this?

Leerhsen: Yes and no. A couple of things you mentioned I think are important. I think Al Stump stumbled onto the same things, but I think he was also smart enough to know that people love a villain. He had that tabloid writer instinct – and by that I mean the National Enquirer kind of tabloid and not the Daily News – of stretching the truth beyond endurance and hitting certain themes and making things and people look a certain way. And one I thing I found was that people not only didn’t object to having the villain, they did it themselves. A historical novelist will take a character and use some of that character’s known attributes and create stories and dialogue and all that, and that’s fine. But other people will do that as well. They tell and retell the Cobb myth over dinner, at a bar or wherever and they will embroider on it themselves. That’s how the racism thing got in there. It’s important to remember that the Cobb myth as we know it, the whole über monster myth, started after his death in 1961. So it surprised me that people really liked the villain story so much that it became like a game of telephone, that old party game where you tell it and retell either to make it sound better or you just get the details wrong and the story changes as it goes along. There were a certain number of people I found that did sense that the story couldn’t be right, that it was too crazy, that no one was like that. It wasn’t very many – a small percentage – but even those people didn’t have an alternative narrative to drop in and so they just kind of left it like that in their mind. Some of them had a connection to Cobb – their uncle knew him or they were from his hometown – but they didn’t have an alternative story.

The Dan Patch story

Open Mic: I learned all those same stories, like that he went up into the stands to pummel a war veteran without arms who had been razzing him. How did you go about separating this widely accepted fiction from fact?

Leerhsen: I’m not trying to be overly modest, but I didn’t do anything genius. I just did the perspiration part that reporters do. All this stuff was back there and could be found in conventional ways. I didn’t talk my way into anybody’s personal letter collection or anything like that. I just found stuff that was there to be found that no one had looked for. And he did go into the stands to beat up the guy you mentioned. But the man, Claude Lucker, was actually not a war veteran, or not that I could find. And he was missing a few fingers as a result of an industrial accident but he had both of his arms. Now I’m not saying Cobb was right to do this, but if you go back and look at the bigger picture you find out that the guy had been harassing him for a year or more. Cobb had even called up into the stands to tell the guy “I’m just trying to earn my living here, give me a break,” but the guy kept it up. On the day of the incident the cops even went in the Yankee dugout there in Hilltop Park in New York looking for the owner of the team. The team’s security person kept telling the guy to shut up and then somebody asked Cobb “how much are you going to take from that guy?” That was the trigger. Cobb went into the stands saying this sort of stupid quote that lived on: “I don’t care if he has no feet.” But what you also see is that when [American League President] Ban Johnson suspended him the next day for doing that, Cobb’s teammates went on strike in support of him. That tells you a lot. The first baseball strike is in support of Ty Cobb, who supposedly didn’t have a friend in the world and who was supposedly hated by all his teammates. People often extrapolate from negative things that [Tigers teammates] Sam Crawford and Davy Jones said about Cobb, and they turned that into Cobb is universally hated by everyone, which is not true. He might not have gotten along with those guys but those guys both had reasons to resent him and did.

Open Mic: What’s your methodology when you go into a project like this where the subject and most of the people around that person might be long gone?

Leerhsen: Well, it reminds me of a conversation My friend John Alter, a political reporter I once worked with at Newsweek, wrote a book a few years ago about Obama’s first year in office. He talked to a lot of people about what went on and of course there was going to be a certain amount of rancor and fighting and contentiousness, which is what makes it an interesting story. He got lots of stuff about what was really going on behind the scenes and the sharp elbows and all of that. He also got access to Obama for two very long interviews. But later he said he so much wished he hadn’t because Obama is a master diplomat and of explaining that things weren’t really conflicts and how something had only been a moment’s flair up and it didn’t mean anything. Now he was stuck with the president’s very good explanation of what people had presented, all great stories of conflict and dishy stuff. But if he hadn’t talked to Obama, when he later went on the radio to talk about the book and they ask “how many times did you talk to Obama, how long did they give you access for?” he would have to say “I had the chance but I didn’t talk to him.” Then he sounds like a madman to the average person. So it is a problem because people then put their spin on it. I had that only to a degree because the people I was tracking down were sometimes grandchildren of major leaguers that had been with or had known Cobb, or others who had known him or whose parents had told them about him. When you write books you have to think in terms of how you are going to publicize your work. Where are you going to be and is this going to be a book people are going to want to talk about on the radio and television a lot? It is hard if you have to say ‘Yeah I wrote a book on this person but didn’t talk to him,’ or ‘I had the chance to but I didn’t.’ But ultimately I just believe you can’t do too much reporting. It’s not just for the facts you get and the data you get from the reporting, it’s from the confidence you get to have when you know your subject and you can say something to the world because you know more about this than probably 99 percent of the population. Facts are important but probably just as important is the confidence you get from having done so much work.

Open Mic: I think every reporter has had the experience where you start out on a project thinking one thing, and the more you peel back the layers of the onion you start to realize it’s something different. What was your thought process when you started realizing this project was really very different? Did it change your outlook on whether you wanted to keep going on with it? You mentioned having commercial concerns, and books are such a huge dedication of life resources, was there ever a moment where you said “This may not be the story I’ll be able to sell?” Or did you say “I found the Holy Grail?”

Leerhsen: Well, I don’t know if I found the Holy Grail. I found this other human being named Ty Cobb who was a variegated, very shaded person. It never felt bad to me. If anything, I felt a sort of relief. It would have been very hard to keep making that same point over and over, that he was a crazy madman. I don’t know if anyone could live with a character like that. The classic way to write paragraphs is you have a topic sentence in which you make an assertion and then you have a piece of evidence to back that assertion up and then you have another piece of evidence and another piece of evidence and then in the very classic, perfect paragraph you end with a quote that complements what you just said without echoing it and maybe even adds a little bit more. If you can do that then you know you can compose a successful story. And it all fit together when I began to see that I had stuck with the idea of Cobb as a monster it just wouldn’t have worked. It was too much. Too many issues would have been left on the side and didn’t fit in the puzzle. And so, figuring out who he was in all these different situations was, was part of the fun.

The true tale of the first Indy 500

Open Mic: And as you showed, he was really a complex person.

Leerhsen: Ty Cobb is a great story. His mother shot and killed his father a few weeks before he came up to the major leagues. When he did come up he was hazed in a way that you know few players ever were before, and he almost certainly had a nervous breakdown as a result of that. And then he turned himself into the greatest hitting machine anyone had ever seen. And because we don’t have the film and no one alive has sat though one of his games, we often overlook that Ty Cobb was probably the most exciting player that ever lived. I can’t imagine a more exciting player than him. Just the way baseball was played back then and how you had to go from base to base. Cobb’s game on the bases was – and this was a revelation for me – really great. As someone said “getting a home run isn’t as exciting as Ty Cobb getting a walk” because home runs are exciting but they’re over in a flash. When Ty Cobb would be trotting to first base, he maybe would suddenly start running at full speed. The fun then had just begun, and everyone would move up to the edge of their seat in the stadium and go “what’s going to happen now?” Because he was full of trickery and getting inside the other guy’s head. He would mess with other guy’s mind and it was exciting to watch as he worked his way around the bases, yelling and screaming and faking what he was going to do. A lot of people in the earlier part of Cobb’s career thought it was unsportsmanlike to behave that way. But he wanted to become what he called “a mental hazard” to the opposition, and a lot of people thought that wasn’t sporting, that he should just let the pitcher pitch and everyone concentrate on their thing. The whole thing about Cobb was that when he was in a game in which the Tigers were very far ahead or very far behind, he would get his craziest. He wanted to plant a little seed in the other team as if to say “this guy will do anything at any time.” That would include barreling into someone with his spikes high. As I say in the book, if there was a statistic for causing errant throws, he would have another record that I’m sure would still stand because he made everybody so nervous. So many guys said, “If he starts stealing second, throw to third” because that was the only chance you’ve got. He was this phenomenon, he was on a different rhythm than other people. He just captivates.

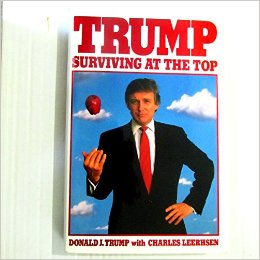

The man who would be king…or a dictator

Open Mic: You spoke earlier of letting the facts guide you on a story. How are you feeling about where we’re at with this “alternative fact” universe we are living in? What impact if any is it having on future considerations for you as an author and a reporter?

Leerhsen: You may not know this, but I was a ghostwriter on a book with Donald Trump called “Trump: Surviving at the Top.” And in the course of that project I would go over there and sit with him day after day, which when on for probably about a year. Most of that time he was in his King Midas period. It wasn’t so much that he was such a success, but he just had this aura about him. He could buy the Plaza Hotel and put one dollar down and borrow the rest and then go buy the Eastern Airline shuttles and put a dollar down and borrow the rest. And of course just like anyone who does that, you better be able to do good business because pretty soon your going to be paying that loan back and then it could all collapse, right? And then he had his first bankruptcies. We had a book written and then we had to redo it in like a week and a half because everything went to hell. I don’t talk too much about it because someday I may write about it. I’m also under contract and I’m not supposed to talk about it, so I don’t say too much about the specifics. But you know he was never very smart. All these people out there in America think he’s a brilliant businessman, they think if you’re rich you must be smart, but he’d be a lot richer if he actually were smart. But I got along with him well. In New York we were what’s called “bridge and tunnel guys” – he was from Queens and I was from the Bronx. So we got along fine and he treated me well. But he’s a moron, and he’s a dangerous moron. He’s trying to run the country like a dictator, like the way he ran his little business where no one knew what was going on but him and he’d look in his cigar box at the end of the day and see how much money he had. In a sense it was like a guy who ran a little store in that it wasn’t very complicated. So you know I’m not surprised by the way he’s acting. It’s exactly the same way he always acts.