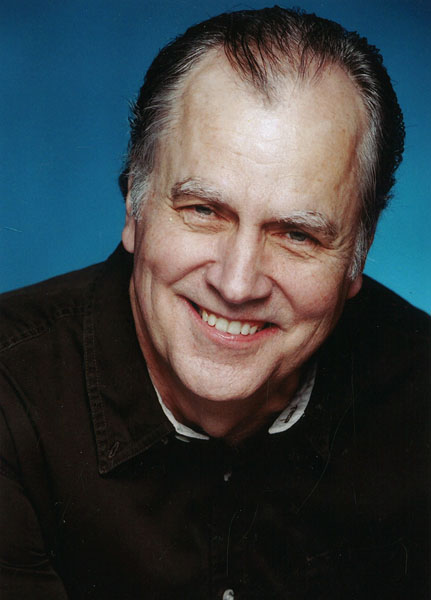

Since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, human beings have been exploring the questions of life through the art and craft of the stage play and its creator, the playwright. While our modern world contains many mediums of expression and communication, there is still something special and unique about the stage, and consequently about the men and women who craft the stories we see there. I’ve had the great honor of knowing one of them, Sacramento’s own Richard Broadhurst, for almost two decades now. He sat down with me recently to talk about the fine art of writing for the stage and screen.

Since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, human beings have been exploring the questions of life through the art and craft of the stage play and its creator, the playwright. While our modern world contains many mediums of expression and communication, there is still something special and unique about the stage, and consequently about the men and women who craft the stories we see there. I’ve had the great honor of knowing one of them, Sacramento’s own Richard Broadhurst, for almost two decades now. He sat down with me recently to talk about the fine art of writing for the stage and screen.

Open Mic: With stage plays everything is about character. What is your process for character development?

Broadhurst: Well, everything stems from character. Because there is no such thing as an original idea. I sometimes compare it to music, maybe because I started life out as a musician. And you know, a lot of times when somebody’s written a new piece of music, some will say ‘it sounds just like’ and then they’ll mention some song. Then I’ll remind them there are only twelve notes in Western music and sooner or later chances are you’re gonna put a combination of notes together that are going to sound like something else.

Open Mic: So you don’t worry about a plot or theme having been done before?

Broadhurst: It’s like at the recent Tony Awards. One of the plays that was nominated, “The Father,” was about a man suffering from dementia. Well, I have a play that’s going to be produced up in Seattle that’s about Alzheimer’s. Now if I made myself nuts and went ‘Oh my gosh nobody’s going to want this play because it’s about Alzheimer’s and there’s this other play that’s on Broadway that’s about dementia,’ I would drive myself nuts. But what makes the play different is the characters that tell the story. In that way, acting served my writing well because once I’ve decided what story I want to tell, I try to figure out who would be the best characters to tell the story. I sit down before I even start writing and imagine that all of those characters are real. They have to be real to me, so I give them a biography. I tell their life story to myself, and once they become real, then they can tell the story. And they do. I have very little to do with the telling of the story. Once I’ve made the characters real, they start to take over really.

Open Mic: You write a whole biography for each one of those characters?

Broadhurst: Certainly for the main characters. It may be only a page or two, but it’s enough for me to know, who they are, where they come from, what kind of family they come from, what kind of issues they’ve had in their lives. You know, what are their biases, what do they believe? I may not use any of that in the play, but it helps me tell the story because I know those characters. It also takes me out of the danger that a lot of writers fall into, which is, if they don’t do that kind of work, all the characters’ start sounding exactly like the writer. You know, they have the same voice, they’re the same, and everything about them is the same. The way they speak, their patterns, everything.

Open Mic: You’ve had plays produced quite a few places. What are some of the theatres that have done your work?

Broadhurst: Minneapolis, New York, Los Angeles, here in Sacramento. I’ve got a play that’s being produced up in Seattle coming up, and there’s a theatre in San Francisco that’s going to be producing a play of mine. Oh, and I had a piece commissioned for a group of high school kids. They did it at Edinborough Festival Fringe in Scotland a couple summers ago. That was fun. I didn’t get to go; I wish I could have. So I guess you could say I’ve had plays produced all over the world. (Laughs)

Open Mic: Is there a particular thing you think is really critical for a playwright to have? I ask that because I think there are certain things you need to do if you’re going to be a novelist, or even a nonfiction writer, and they’re all a little different. Is there something that you feel like is true for playwrights as well?

Broadhurst: I can’t speak for every playwright, but I do think that theatre is the place where there’s more emphasis on ideas. It’s a little bit more editorial than novels or film. For sure, theatre people want to entertain an audience, but a lot of theatre wants to kind of challenge an audience and engage an audience and create some sort of dialogue for an audience so that when they leave the theater they’re still talking, not necessarily just about what they saw, but maybe what they believe. I feel like my job is done even if someone leaves the theatre and they hate the play but they’re still arguing about the topic. For me, that’s become much more important than them loving the work. Obviously if they love the play it’s going to probably feel better, but that’s okay if they don’t.

Open Mic: Are you drawn to a particular kind of story more than others?

Broadhurst: Yeah, I am. I had sort of a scary experience about 15 years ago where I almost died because of some botched surgery, and it made me rethink what I wanted to write about. So I am much more inclined to write about things that matter to me and to try to hopefully create some kind of change or get people to rethink things. You know, like the events that happened in Orlando. Things like that always stir me to write. I guess I’m attracted to anything that deals with intolerance or injustice. Family things also interest me, especially dysfunctional family stuff, because there is so much of it and so little of it is ever really exposed. We’ve all sort of been, “what happens in the family stays in the family” and nobody really talks about the crap that goes on. I was commissioned once to write this piece about Ted Kennedy. I didn’t know that much about the Kennedys personally until I started working on this piece. I knew about the politics and a little bit, but their family was just as dysfunctional as any normal family, in some ways even worse. I could certainly make the case that the children were pretty severely abused emotionally by both the father and the mother. To which most people would go “really? How could that be?” But you know that’s what binds us all together to some extent is that dysfunctional stuff.

Open Mic: Are you talking Rose and Joe?

Broadhurst: Yes. I mean, Joe had one of his daughters (Rosemary) lobotomized because he was afraid she was getting to an age where she might accidentally get pregnant and he didn’t want to have to deal with the scandal. And when Ted and one of his sisters misbehaved as were children, Rose would lock them in a dark closet and keep them in there until she thought it was okay for them to come out. And of course the womanizing. You know, it’s also no big surprise at all that all the Kennedy men were womanizers because that’s what they saw at home. Joe used to bring his mistress for dinner.

Open Mic: Who are some of the playwrights that have inspired you, famous or otherwise?

Broadhurst: Later in life I became very impressed by the work of William Inge. Partly because he’s from Kansas, as I am, and I like that there’s a lot of subtlety to his work. He’s not as splashy as say, Tennessee Williams, but he really understands that whole dynamic of family and dysfunction. And I like Sam Shepard a lot. I also like David Mamet because his language has its own sort of bizarre beauty to it.

Open Mic: With Mamet, everything is about language.

Broadhurst: I think it’s true for all the great playwrights. Every once in a while I’ll teach a screenwriting class, and people will say, “How do you know the difference between whether you should be writing a play or a screenplay?” And I say, “Well, it’s actually pretty simple, “It’s the characters.” If most of your characters tend to want to talk to one another, you’re probably writing a play.

Open Mic: You also do screenplays. Are screenplays more liberating? What do you feel is the big difference for you as a writer when you approach a screenplay as opposed to a screenplay?

Broadhurst: I like writing screenplays but I don’t particularly find them liberating because in a way they sort of rob me of the chance to be more imaginative. It’s harder to suspend disbelief in a screenplay. I also know that most of my screenplays are never going to be done the way I want them to be done. And because I’m a writer for hire, if somebody buys my screenplay, they’re going to do whatever they want with it. So I generally don’t have any control, whereas with a play I have all the control.

Open Mic: Now that’s interesting, when you write a stage play, they are bound to stick to what it is you’ve written?

Broadhurst: Oh, absolutely. They can’t change anything. There’s the Writer’s Guild for screenwriters, and playwrights have the Dramatist’s Guild. The reason playwrights did not want to have a union was because once you become a union, then you’re sort of a writer for hire. Whereas playwrights are not for hire. You can buy my work, but you have to do it the way I write it or I can shut you down. If you don’t do it, if you change anything. You have to get my permission first.

Open Mic: I have definitely now learned something.

Broadhurst: Writers have actually shut plays down if their plays are not done the way it was written. Some are pretty adamant about it. They’ll track you down and make sure you’re doing it the way they wrote it.

Open Mic: We’ve seen a lot of great plays made into movies. What are the main similarities and differences about how you go about doing a screenplay as opposed to a stage play?

Broadhurst: Well, it depends on who they allow to write the screenplay. If the playwright is allowed to write the screenplay they can be pretty close. But for years Hollywood was so obsessed with happy endings that really interesting characters were often eliminated. I talked about William Inge. Every one of his plays that was converted to a screenplay was just ruined that way. They took out elements of the story that were so important. It was very disappointing. Even Tennessee Williams had stories turned into happy endings. In “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” there was a whole storyline about a gay relationship between two of the main characters, and that was just completely shifted to avoid any mention of someone being gay. The implication was clear in the play but they just got rid of it in the screenplay. I’ve certainly taken a couple of my plays and turned them into screenplays. In some ways it was fun but I also knew I had to open it up, which took away some of the parts that were more fun for me, the imagination.

Open Mic: Are there playwrights now that you think are really impressive?

Broadhurst: You know, this is going to sound funny. Maybe because I do it, I don’t like going to the theatre. It’s my job and I don’t want to go to my job, so I tend not to go to the theatre very often.

Open Mic: Is it stressful for you to feel like so much of the success of your work is so dependent on how others interpret it and then project it to the audience?

Broadhurst: It depends. Usually I’m involved in the casting, but if I’m not, or if I’m overruled, it can be very stressful. If you get good actors they can make all the difference. I love the rehearsal process. I do a lot of rewriting in rehearsal because I can tell when an actor is having trouble with a line. I can usually tell if the line is written poorly or there’s something wrong with the rhythm of the line. Or the actor will sometimes even say, “you know, I can’t quite get this line to work.”

Open Mic: That’s great you actually get to work with that interpretation of your work.

Broadhurst: Oh yeah. That’s another thing I love about the theater. With films it’s pretty rare to even have a screenwriter on the set.

Open Mic: Yeah, I imagine they would consider you more of an annoyance than a help.

Broadhurst: Theatre is a playwright’s medium and film is a director’s medium. That’s the difference. And it’s sort of irritating. The next time you read a review of a film, if it was a great film they’ll talk about the director. If it’s a terrible film they’ll talk about how awful the script was. So they never mention the writer unless the script is terrible. But if it was a great film, then it was the directors doing.

Watch for Richard Broadhurst plays in the coming months at the ACT theatre in Seattle and the Lorraine Hansberry Theatre in San Francisco.