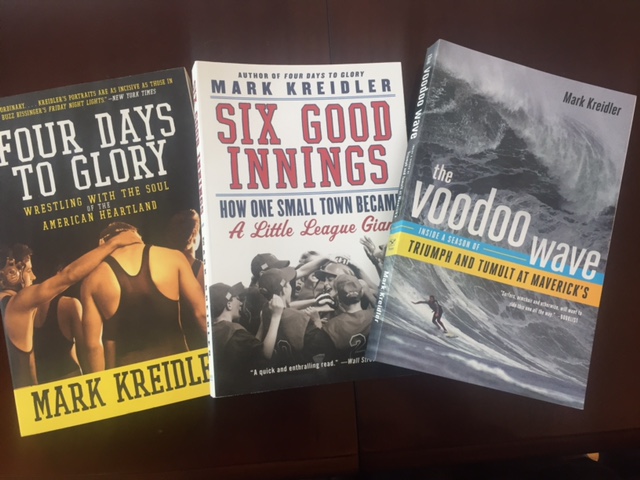

From his early days as a reporter with the Associated Press in Oklahoma, award-winning sportswriter and columnist Mark Kreidler has always been a great storyteller. But while he has covered the  biggest names and events in sports, as an author Mark has always been drawn to smaller, more unique stories that allow him to showcase people and events rarely given much play in the big time sports media machine. Those works span the highly acclaimed “Four Days to Glory,” a story of high school wresting in Iowa, to “The Voodoo Wave,” which chronicles the thrill seekers – some might say crazy people – that ride the monster waves Mavericks Surf Contest at Half Moon Bay. Mark was kind enough to sit down with me recently to talk about his work and why there’s never been a better time to be a writer.

biggest names and events in sports, as an author Mark has always been drawn to smaller, more unique stories that allow him to showcase people and events rarely given much play in the big time sports media machine. Those works span the highly acclaimed “Four Days to Glory,” a story of high school wresting in Iowa, to “The Voodoo Wave,” which chronicles the thrill seekers – some might say crazy people – that ride the monster waves Mavericks Surf Contest at Half Moon Bay. Mark was kind enough to sit down with me recently to talk about his work and why there’s never been a better time to be a writer.

Open Mic: The transition from daily news to the long haul of books is really interesting to me. Is that how you envisioned you would go, from news reporting to author?

Kreidler: Growing up, all I ever wanted to do was write. I always thought I would write books, but I never thought about when. It was the last thing I was thinking about. I just wanted to write. Like a lot of people I wound up in newspapers because it was the path of least resistance to that goal. I also didn’t grow up thinking, ‘gosh I hope one day I can write about sports.’ I loved sports, but I only wanted to be a writer. I didn’t really care what. My first job was for the Associated Press. I was an intern at the AP in college and they offered me a full time job before I graduated, so I had already begun my career when I was a senior in college. At the AP, by definition you wear every hat. And I loved it. I grew up in Oklahoma, so I’m working in the Oklahoma City bureau of the Associated Press in a windowless space of the Daily Oklahoman building, which at the time had been proclaimed the worst daily paper of the major metros in the United States. We weren’t even in the view there, we were in the basement. One day I’d be out at the state capitol, then one day I’m writing a labor story, and another day doing a tornado alert. It was all interesting to me. So I always figured I would write a book at some point, but I didn’t think it would be nonfiction. I think people grow up thinking, ‘I’ll write the great American novel.’ Well, maybe you will. But maybe the opportunity that presents itself is something you never expected. I never thought about the sequence at all. To put it in my world, it would be like saying, ‘you’re a really good second baseman, let’s make you a pitcher.’ They’re the same sport, but that’s a really different skill set. That’s how I feel about when I started that first book, there was definitely a step back.

Open Mic: How do you wrestle all your ideas down and decide what one you’ll work on over the next many months or years to get it from cradle to grave?

Kreidler: That’s a special question because you’re ultimately talking about time out of your life. I’ve certainly had ideas. There was a big benefit to having been a columnist for as many years as I was. Before that I was a take-out writer, which is an old newspaper term that just means a long feature. No one says take outs anymore because newspapers don’t do them. But because of all of that, I was accustomed to knowing what a small idea was, because a columnist functions on small ideas. When I get my Monday column done, I would immediately start thinking about what I would do on Wednesday. These are all small ideas. And as a daily columnist, you are always immersed in the idea of advancing the story. Can I take the story forward one iota? That’s today’s challenge. With a book, you’re stepping back and saying, ‘what’s my big thought?’

Open Mic: Is that how you developed “Four Days to Glory?”

Kreidler: I had an agent who had been introduced to me, and while we weren’t doing anything together yet we were talking. He’s a really bright guy and was a longtime book editor before he went to the agent side. To answer your question I thought I had a small idea. Wrestling in Iowa is as obscure as it gets. Sports Illustrated had a one page story on the Iowa State wrestling tournament and it had always struck me that the Iowa State wrestling tournament gets 130,000 people going to this thing and filling up the building for five days in a row. The tickets sell out months in advance. I mentioned it and said I thought it would be a really good longer magazine piece than what SI did. I asked for his help in finding a magazine like The Atlantic that would say like it as a slice of Americana. He called back and said, ‘I think it’s a book.’ So sometimes you don’t even know as a writer. So, I was lucky there. He sold it to Harper Collins. David Mercy was the editor at the time. And off I went. The one thing about it, “Four Days to Glory” and “Six Good Innings,” both were getting at things that I find very interesting. The little league kids are younger than the high school kids, but in both cases, these were stories on two different levels about how small towns often use sports as connectors, either to each other or fathers to sons. The other thing was, I coached little league for a long time and traveled along and all that, and I find it fascinating when people want kids to peak at an early age. In little league, you’re supposed to peak at age 12. That’s a weird concept. In Iowa, the notion was these kids could become nearly immortal. And honestly, their names are still on the wall and will never come off for having achieved the things I wrote about in the book. They were aiming for almost a career peak before they even got out of high school. It’s a unique set of pressures.

Open Mic: It’s kind of a weird dynamic that we have people for whom life seems to peak at 18 or younger.

Kreidler: Yeah, I was fascinated by it. I had young kids at the time, and I just thought, it’s an extraordinary thing to ask. Not too many kids at that age are going to perform in front of that many people. Growing up in Oklahoma, I felt very familiar with all of that because we had no close sports growing up in our state. High school stuff was huge, college stuff was huge. You could see how families often used sports to replace language at times when they struggled. That’s certainly what I ran into in those books.

Open Mic: Do you surf? How did you say, I want to write a book like “The Voodoo Wave,” which is about the crazy big wave surfers at Mavericks?

Open Mic: Do you surf? How did you say, I want to write a book like “The Voodoo Wave,” which is about the crazy big wave surfers at Mavericks?

Kreidler: I’m a surfer of memory now. No claim. But I lived in San Diego for 10 years before we moved up here, worked for the Union Tribune, so I’m really familiar with the culture and have some friends that are blond surfers. So I certainly felt at least a little familiar. I guess its, obviously I’m drawn to really rich subjects. I’m probably the least likely person to write the fourth biography of Bill Walsh, or something like that. I’m never going to write that book. It just doesn’t interest me because it’s been covered by everybody. But I love the things I write about in the surfing book because it’s about guys who take really big risks in pursuit of, well, I wasn’t even sure what. I thought they were thrill seekers, which obviously they are on some level, but its way deeper than that. It’s very spiritual and deeply connects them to their world. I wouldn’t have counted on that. I was locked into surfer dude mode when I started the book, so I thought I was just writing about an extreme sport, but I really wasn’t. I was writing about what is for a lot of those guys a spiritual passion. I was really just drawn to it because I thought it was an underexposed story. That book about kids in Iowa, I promise you that’s the only book that’s been written about wrestling in Iowa. This one little league town in New Jersey, within the little league culture, people know all about Tom’s River, but certainly no one would have written a book. And I’m drawn to that because, you don’t need me to tell you the Cowboys were great back in the day or about how we can’t forget the Yankee Dynasty when there are already a billion books about it.

Open Mic: So you have no interest at all in mining some of the popular stuff?

Kreidler: Some of it. Part of it is I wrote almost everything I knew as a columnist. I wrote everything. Some of it might be book worthy. I could go back and write a wonderful book about a lost team, for example. I covered some bad teams. But I don’t think I’m a conventional sports writer in that I tend to like lesser themes. I like minor themes a lot. I sometimes find myself drawn to the corner of the story, rather than the center. Jeff Pearlman wrote a wonderful book about Roger Clemens. My favorite pitcher when I was a kid was Bob Gibson, but I never wanted to write a book about him. I find myself drawn to those areas where sports and culture intersect, or sports and ordinary human life intersect. I’m not often drawn to where sports and superstardom intersect.

Open Mic: I can understand. I always thought I would love covering sports, but after doing it for a few years I hated it. It’s weird how things work out. The point of that is, there’s so much that happens behind the façade of sports. There’s a line of what you can actually put into a column to maintain a trust with the audience and with the subject. Did that differ at all for you as a sports writer than as a person writing a book? Did that evolve at all?

Kreidler: It did actually, partly because most sports writers who are working in bigger markets are covering pro athletes. With pro athletes, the code is pretty straightforward: ‘are we on the record or off the record?’ I found it to be way too confusing to have someone try to move that line on me all the time. My understanding with everyone I ever dealt with was that we are always on the record. You’re talking to a reporter. If you don’t want it written, don’t say it in front of me. Don’t come back later and say, ‘hey this part if not for print.’ You can’t do that to me. If you have a very special exception, you can always come to me and say, ‘hey can we talk off the record?’ But if I come up to you, even to say hello when you’re at practice, we’re at the workplace and you should assume it’s on the record. If you go into a book, you can’t lay down those sorts of ordinances and expect to really have a conversation that would be meaningful enough to produce anything. So I think in a lot of cases with all three of the books I did quite frankly involved a lot of hanging around. The front end of those books was an awful lot of time spent with no notebook out and no tape recorder on, nothing more than me being there. Because it sometimes took weeks or months or develop a relationship and trust with the people.

Open Mic: Especially in small towns.

Kreidler: Yeah. To the point where they would feel comfortable sharing anything with me that would be of true value. So it’s odd, but I’m a big proponent of hanging around. Loitering essentially. I think you have to. And then, and only then, can you proceed with a little bit of trust with the people with whom you’re speaking. Part of that is they’ve gotten to know you well enough to believe that you are not there to harm anyone. I had some difficult situations in the wrestling book and the little league book where I had to go to a couple families and say, this is kind of painful but I think we should include it. Not that it was a collaboration but I want to write this, and I want you to understand why, and I want it to be okay. Daily journalism, no one has time to say, ‘hey, let’s go have coffee so I can explain why it’s really important.’

Open Mic: But at the same time, if it’s a daily, you’ve already had a chance to build all that up. So in this, you’re starting from ground zero.

Kreidler: Oh yeah. When I was a very young reporter, I was covering a baseball team as a beat writer. You see them from February to October. You’re with them all the time, and over time I had people walk amazing stories right up to me and put them in my lap. But that’s because they knew me. This is a totally different process where you’re trying to accelerate that getting-to-know-you process and it’s very difficult. At some point, I think you have to immerse yourself. I think if you don’t immerse, you’re lost. I moved to Iowa. I left my wife and kids for two months, and I had already done the ground work, I’d been back there and introduced myself and all that. But when I went to be there, I really went.

Open Mic: Did you already have a contract at that point?

Kreidler: Yeah. I’m not big on working without a contract. For two reasons. One, I think for a writer, it’s silly. If you’re writing a novel, knock yourself out. But if it’s a nonfiction work, you should really know that it’s publishable. And secondly, I like deadlines, and contracts have deadlines. Deadlines are good. Ticking clock is a good thing for a writer. So yeah, when I went back to Iowa, I was under contract.

Open Mic: Have you ever met anyone whose biography you might do?

Kreidler: I don’t know. I won’t say never. I think as writer you always have to leave yourself open to the possibility that someone might say something that you hadn’t thought of. You have to be willing to say, ‘just because I didn’t think of it, it might still be a great idea.’ I’ll never say never. But yeah, I’ve been so lucky in my career, the guys that I’ve been around in sports, a lot of them are fascinating people. Many of them are so well known that it’s hard to conceive of writing a book that would produce anything worthy. I bet I could make money, but I don’t know if I would produce anything of value. I got to know Steve Young really well, but his story isn’t a mystery to anyone. I’ve known Bruce Bochy since he was a player, and I think he’s a fascinating guy and a highly underrated expert. I don’t want to write his biography, but I’d love to write a book with him about why he sees baseball the way he does.

Open Mic: A “Men at Work” type of book.

Kreidler: Yes. Those are my kinds of guys. He’s easy to underestimate. I was just reading something yesterday that Brandon Crawford wrote about being a Giant. He was referencing something about Hunter Pence. Everybody knows Hunter Pence because he just puts itall out there. Brandon was making the point that Bochy delivers messages that are incredibly valuable but you won’t ever know, because he delivers them to us in a low key style. And he said, then we get Hunter, from a totally different perspective, with this wild man, emotional, live out loud kind of thing. I love that idea that those worlds collide.

Open Mic: What are the things that you need to have when you write? What’s your process?

Kreidler: I’ve had really different experiences. The first book, our two sons were pretty young and when I came back from Iowa I came back to an awful lot. I was alone when I was there so I had transcribed everything, and when got back I was ready to write. Let’s go, I’m ready. I had a friend here in town who had an office that didn’t get used at night, and he gave me a key so I went up to his office to work. It was some agriculture related shipping business. In other words, the least interesting office you can ever describe. You walk in, there’s a couple of desks and a computer terminal and a picture of cornfield. Nothing in it. And it was ideal. When I got there, there was never any question that I had gone there for one reason. I went there a lot, I worked there late at night even though I’m a morning person, because that’s what was available to me. But from there I started to realize that my process was the less the better. By the time I got to the surfing book, I rented a space at a little office building that wasn’t much bigger than the smallest apartment bedroom you can think of. It was incredibly cheap, it didn’t have wifi, it didn’t have anything but white walls. I bought a cheap desk and a decent chair, and that’s how I wrote that book. If I could build you my perfect writing room, it would be bare white walls and not much of a view. I think nowadays we’re more easily distracted and our attention span is more of a challenge than ever. I’ve been writing for a living most of my life but I find it harder to sit and read than I ever have. So I understand. And I think it should influence the way you write. You should be smart enough to grasp that if you, a dedicated reader, don’t necessarily always have the patience to read a long piece, maybe you should write shorter. Maybe your chapters should be shorter. Maybe you should give somebody something that they could get through three chapters in nine minutes because each chapter is only four pages. I don’t know. I remember reading “The Da Vinci Code” when it first came out and thinking, ‘these chapters are really short; this is really smart.’ So for me, that all goes back to how I work. It’s all about attention span. I put myself in the blandest situation possible. I just don’t do well with distractions. It takes everything that I have to get it right. We’re writers. We’ll take any excuse under the sun not to do it. ‘Man, my coffee is cold, this isn’t going to work.’

Open Mic: What’s your sense of how the industry is now? Better off, worse off?

Kreidler: Better. In my opinion, it’s never been better, even though the publishing industry is just in total chaos. I say this as someone who has been incredibly lucky. My first book proposal was the wrestling book. I’d never written a book proposal in my life. My first proposal fell into an international publisher. My three books went Harper Collins, Harper Collins and W.W. Norton. I’ve had three unbelievable experiences, major publishing houses with their armies of PR people and book tours and the whole thing. I got the great ride. But if I was coming out today, it’s unbelievable. You can create a template for your book in about 9 minutes online. I’m not saying it produces great literature – as writers we know that we hope no one ever sees 90 percent of what we write – but if your goal is to write something and give people the opportunity to read it, the opportunity is there.

Open Mic: Editors exist for a reason.

Kreidler: Agreed. And that’s what traditional publishing gave me. In the same way that a sports fan can hate another team – meaning they don’t really mean ‘hate’ – I hate editors. Bane of my existence. Hate them. They get things wrong, they misrepresent my intent, my tone, whatever. But they’ve saved me a million times. The editor on my first book was probably the smartest guy I’ve ever worked with and he made me think very differently by the time we were all done. He beat me up. It was a tough go. He was just phenomenal. I find them to be a necessary evil. That part gets lost if you’re self-publishing. But the opportunity is unbelievable for someone coming in. You can actually circumvent the entire New York publishing process, because that’s a tough process. That’s a process of having an idea, flushing it out into a massive book proposal, I would say 99 percent of the time needing an agent, and then having it go off into some ether for 12 or 18 months while a publisher takes a meeting or takes a look at it and advances it to a second reading and goes into a group reading. In that amount of time there are people in Sacramento publishing online who have written four new books. So it’s like the Wild West right now. Everyone is in a land grab. It’s almost like, if you get there you can have it. If you carve out some niche that I’ve never thought of, the undead soccer team from Pluto and there’s a market for it, it’s all yours. And there won’t be anybody sitting in an office in New York saying, ‘I don’t understand it.’ I would imagine for younger writers especially who don’t have any of the preconceptions that I grew up with, I think that’s so cool. The first time I walked into a publishing house in New York, I was thrilled. It was an ordinary building, but it didn’t matter to me. I’m walking into Harper Collins, are you kidding me? It’s like walking among the gods. But for anybody coming up behind us, they’re not impressed. They’re more like, ‘how am I going to achieve my goal?’ They have far more ways to achieve their goal than we did. I don’t know for a fact but I wouldn’t be surprised if I’m one of those people publishing directly to Amazon.

Open Mic: And you already have the audience to do that. Why go through a publishing house when you already have the audience?

Open Mic: And you already have the audience to do that. Why go through a publishing house when you already have the audience?

Kreidler: I’ve been surprised by the number of people who, with absolutely no name, have gone into the humor world, for example, and found an audience. There are a couple of people in Sacramento who just threw it out there and were shocked that they sold anything, and then sold more and more. Remember, the flip side of traditional publishing is they want to publish the hardcover copy at $26.99. Well, nobody’s buying that. That’s the reality. So with Amazon, there’s always that thought of, ‘I love this and I want a publicist, but I’m only going to charge $4.99.’ You’re just inviting more people to share your work.

Open Mic: And its economics.

Kreidler: The royalty schedule in traditional publishing is just insane.

Open Mic: And they charge you for everything.

Kreidler: Yeah. But I wouldn’t trade it, because I had the experience of a lifetime. We went on real book tours. The way I thought it would be like was how it really was. Some days good, some bad. You’d walk into a book tour and there’d be four people for a scheduled signing, but the next night there’d be a full building. It was amazing. We also did traditional media tours. It was very exciting, and that’s the kind of thing you can’t experience any other way. But I just don’t think that model works anymore.