Author Ed Ruggero has spent a lot of his adult life studying what makes a good leader, be it in business or on the battlefield. A West Point graduate and military veteran himself, Ed has taken special interest in showcasing the stories of some of the courageous airborne troops who made numerous combat jumps across Europe in World War II. Those stories are the inspiration for his new book, BLAME THE DEAD, his first work of fiction in quite a long time.We sat down recently to talk about his work, the power of leadership, and the special care required when interviewing military veterans.

Author Ed Ruggero has spent a lot of his adult life studying what makes a good leader, be it in business or on the battlefield. A West Point graduate and military veteran himself, Ed has taken special interest in showcasing the stories of some of the courageous airborne troops who made numerous combat jumps across Europe in World War II. Those stories are the inspiration for his new book, BLAME THE DEAD, his first work of fiction in quite a long time.We sat down recently to talk about his work, the power of leadership, and the special care required when interviewing military veterans.

OM: Your new book BLAME THE DEAD is your first work of fiction in a while. Tell me a bit about it.

ER: One of my non-fiction books is set in Sicily, about the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943. Blame the Dead is set in that time and place as well, so I was familiar with the setting and the people and the bigger picture. But in doing the non-fiction work there were lots of stories that were never going to make it into that book, lots of fragments of stories and things that I learned that I wasn’t going to use in a non-fiction book. So doing fiction just gave me an opportunity to use all that stuff. It gave me a lot of latitude. I could create characters who had experiences that I heard from four different people, and combine them into one character. I could play a little bit with the timeline and bend a little bit about what actually happened on a bigger scale and make it fit what I wanted to have happen on a smaller scale. So it just gave me a little more freedom. My approach to non-fiction is that it has to be a great story as well, so I’ve never really strayed too far from storytelling. It’s always all about the storytelling.

ER: One of my non-fiction books is set in Sicily, about the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943. Blame the Dead is set in that time and place as well, so I was familiar with the setting and the people and the bigger picture. But in doing the non-fiction work there were lots of stories that were never going to make it into that book, lots of fragments of stories and things that I learned that I wasn’t going to use in a non-fiction book. So doing fiction just gave me an opportunity to use all that stuff. It gave me a lot of latitude. I could create characters who had experiences that I heard from four different people, and combine them into one character. I could play a little bit with the timeline and bend a little bit about what actually happened on a bigger scale and make it fit what I wanted to have happen on a smaller scale. So it just gave me a little more freedom. My approach to non-fiction is that it has to be a great story as well, so I’ve never really strayed too far from storytelling. It’s always all about the storytelling.

OM: Two of your previous books deal with paratroopers in WW II, specifically the often very young men who made historic jumps into Sicily and at Normandy. What was the inspiration behind those efforts?

ER: In 1998 I was up at West Point researching a non-fiction book about leader development at the military academy. I had been out in the field all day with the new cadets that were doing basic training. I went back to the hotel about 5:00 in the afternoon, and I’m sitting in a lounge, the only person there in the bar. This fellow walks in and even if we had not been at West Point, I probably would have picked him out as a soldier. He was about 80 years old, and he’s got this direct stare. He strides right up to me, sticks out his hand and says, “Jack Norton, pleased to meet you.” I said, ‘Sir, have a seat and let me buy you a drink.’ He’s got on a conference nametag that said Jack Norton 41, meaning West Point class of 1941. We start chatting, and it turns out that he served in the 82nd Airborne Division throughout the entire war. He made a combat jump into Sicily in August of ‘43, a combat jump into Italy in September of ’43, a combat jump into France in June of ’44, a combat jump into Holland September of ’44, at the Battle of the Bulge, and then the 82nd airborne division was selected to be America’s representative force in Berlin, which of course was captured by the Soviets. So this was a guy who had been a couple places and had done a couple things. And he was a great storyteller, especially after two Manhattans.

He started telling me about invading Sicily, where just about everything went wrong and yet they managed to complete their mission. And I asked him, as a former soldier, how do you do that? He said it takes good soldiers and it takes good training. You’ve got to watch them, you’ve got to coach them, you’ve got to trust them, and you’ve got to put them in charge because paratroopers are frequently scattered around the battlefield and they have to take charge of their own little circle of the war. And that takes good leadership. So then we talked a lot about his commander, a guy named Jim Gavin who was a colonel at the time he jumped into Sicily. I asked what Gavin was like as a leader, and Norton paused for the first time and he looked at me dead in the eye and said, “he set us on fire.” And I was just smitten with that story right from there. Jack Norton introduced me to a bunch of the other paratroopers, and I started interviewing them in the summer of ’98. I just followed that trail. It’s been a highlight of my entire professional life, certainly as a writer, to talk to these guys and be entrusted with their stories.

OM: I’ve taught seminars on interview techniques to writers a few times over the years. It’s hard sometimes for people to understand that different situations can call for different methods. How did you prepare yourself for interviewing these men? Did you do anything differently than you would in speaking to other subjects?

ER: With this generation of men I would start with a letter, on paper, that would get delivered to their mailbox to introduce myself and talk about what I was up to. I would ask if we could then meet in person, depending on where they lived, or at least talk on the telephone. There are two aspects of their experience that had an impact on their interviews and the way I interviewed. One is this generational idiosyncrasy that they didn’t talk a lot about emotion. I got to talk to Dale Dye, who was Steven Spielberg’s military advisor, and we were talking about his work with “Band of Brothers.” He said the actors would ask, “what did you feel like?” And these real soldiers would say, “I felt like I should run because they were shooting at me.” So emotions were something they didn’t just talk about handily.

The other thing is that a lot of these men had never talked about these experiences with anybody, and many of them were traumatized at that time during World War Two. A lot of that came out in the interviews. So I learned to be patient. If I’m interviewing someone for some other non-fiction work and I’m asking you about your job and the interview starts to go off into one direction, I might ask a couple of questions to get it back on track. But with somebody that’s talking about an event that clearly was an epiphany or a low point in their life, I just have to be patient and let them talk it out. I might make a note to circle back later and pursue some line, but they would give me the story. The stories might be disjointed, but I just had to be patient and take notes and then go back and put them together and just work with them. But a lot of these guys got very emotional as I was doing these interviews. Even 55 years after the end of the war, for many of them it was an emotional experience.

OM: Was that experience emotional for you?

OM: Was that experience emotional for you?

ER: It was, though it was obviously much more emotional for them. I wanted to be respectful of that. I never wanted to give the impression that I found it exciting in a weird sort of way. I always say that my job as a historian is to pay homage to what they did without ever glorifying what they went through. At the end of Combat Jump, the book about Sicily, I quote one of the soldiers who said, “It’s just something terrible that happens to young people who have nothing to do with starting it. It’s all waste and if there’s anyone who thinks there’s glory attached to it is a fool.” I always try to be respectful and keep that in mind. It’s possible to tell these stories without ever making it sound like fun.

OM: What is the most surprising thing you learned from your research?

ER: That these guys were amateurs. They really were just making it up as they went along. The US military went from being ranked something like 19th in the world in the late 30’s – behind traditional military powerhouses like Portugal – and by 1944 there were about 10 million American citizens in uniforms. So they were amateurs. They’re good-hearted, they’re smart, they’re intent, but they’re amateurs and they’re just making stuff up. I was talking with one of the paratroopers about how to get supplies quickly. The plan was to drop it out of an airplane, and he said they should color code the parachutes so when the bundles are coming down the guys could see what they were. And I said that’s a good idea what made you think of that? He said “my mom owned a fabric store and she used to dye fabrics.” That just drove home that they were just making stuff up and if it worked, good. There was a famous quote from a German general that said, “don’t study American doctrine because the Americans don’t study it themselves.” And that’s partly true because what you had was a bunch of citizen soldiers stepping up. So the enthusiasm and amateur-ness of the forces always surprised me. In fact, in Blame the Dead, one of the characters was in the regular army before WW l, and he complains all the time about “a whole goddamn army full of amateurs.” It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it’s true.

OM: You’ve noted that military fiction often tends to oversimply warfare. What do you mean by that?

ER: In both fiction and non-fiction, we dignify war. We sterilize it. If you look at war movies from the 50’s, somebody gets shot and they fall down but there’s no mess and there’s no blood. Paul Fussell – who was an infantry lieutenant wounded in Europe and who later became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and won a national book award for one of his books – talked about how it’s not like that at all. It’s awful and it smells bad and it’s terrifying. So if you have someone with a pistol that fires 60 times without reloading, or some protagonist dispatches seven enemy soldiers and it has no effect on him and the next thing you know he’s having drinks with his honey, that’s campy and ridiculous. And that kind of stuff bothers me, and I generally will stop reading if we get to that. Being in combat has an effect on people, especially close combat, and downplaying that is disingenuous and disloyal to the people who went through it. So that’s something that I try to get right in my own writing, and I hope I’m doing that. I think I got it right in my nonfiction because the paratroopers told me that I did a good job, and that was huge for me.

OM: Was there ever concern on your part when you started doing it over how you were going to top something as historic and as lasting and as enduring as Band of Brothers?

OM: Was there ever concern on your part when you started doing it over how you were going to top something as historic and as lasting and as enduring as Band of Brothers?

ER: Band of Brothers was only a book at the time that I started writing Combat Jump. The series wasn’t released until 2001. In fact, the first episode aired the night before 9/11. I think probably every author labors under the concern of “I wonder if anybody else is writing this and are they going to beat me to it?” But once I got a hold of the story, I wasn’t going to let it go. When you write your book proposal, you’re going to say this book is like this other book which has done really well but it differs in this way, so I don’t think that weighed too heavily on me.

OM: What is the primary audience for your nonfiction works? Do you think most of those readers are former military themselves? And how, if at all, does that impact how you address your material?

ER: I think that readers are from the general population, and they have an interest in history. They have an interest in military history with fiction. They just want a good story, something that’s dramatic and characters they can care about and cheer for. I do try to get the little stuff right. My wife won’t watch any movie or TV show with me that has military people in because if their insignia is upside down, or if they’re holding their weapon incorrectly or something, I just can’t let it go. But the audience I have in mind when I’m writing is the general audience because of course the vast majority of Americans don’t have personal experience with the military.

OM: You have a lot of irons the fire – teaching, speaking, etc. What is your writing schedule like? Do you have a set routine you adhere to?

ER: I was in the military so I’m pretty self-disciplined. When I’m writing I write at the same time during the day. The morning is the best time, so I set that time aside. I turn the phone off, I turn email off. I typically will get up early, exercise, walk the dogs, shower, eat breakfast, and then I’m at my desk and I try to get in for or five good hours. The afternoons are for revision and email and research and those kinds of things. I generally don’t trust anything I write after say 2:00 in the afternoon because it’s not my best brain time. So I am aware of when I am most productive and I do try to keep that time sacrosanct.

OM: You focus so much on leadership. That topic is a pretty crowded field. How do you make your work stand out from the pack?

OM: You focus so much on leadership. That topic is a pretty crowded field. How do you make your work stand out from the pack?

ER: In my business I run retreats with business executives and teams, and we go to battlefields where I use history as a launching point to talk about leadership. I live in Pennsylvania so Gettysburg is one of the places I go most often. You don’t have to be a history geek, and you don’t have to know a bunch about the Civil War. Fundamentally everything I do is built on my ability to tell a story, so I can bring you to Gettysburg and make you see and feel and hear what these people were going through. And then together we can figure out what can we learn from them that can help our modern organizations.

OM: You were in the first class at West Point to include female cadets. You’ve also noted the important role women played in events like those you chronicle in both your fiction and nonfiction books. Do you have any plans to do a nonfiction project that explore the role of women in the military in greater detail?

ER: I wrote about women at West Point in my book Duty First, which is about leader development at West Point. I got to spend some time with some wonderful young cadets, men and women, so I wrote about them there. It certainly has influenced my work, and you should never say never, but it’s not on my radar right now to write specifically about that. There are a lot of really smart women who have personal experiences who are writing about that stuff and I’m happy to defer to them.

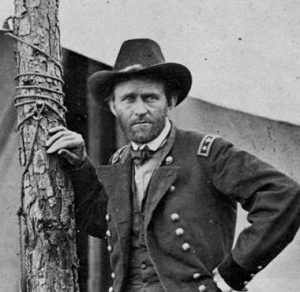

OM: I like to end on what I hope is a fun question. Let’s say I can put you together with just one person of the following people for a great conversation. Who would you choose and why? Your options are: Ulysses S. Grant, Opha May Johnson (the first female U.S. Marine) or Joan of Arc.

OM: I like to end on what I hope is a fun question. Let’s say I can put you together with just one person of the following people for a great conversation. Who would you choose and why? Your options are: Ulysses S. Grant, Opha May Johnson (the first female U.S. Marine) or Joan of Arc.

ER: Maybe this is predictable, but I would have to go with Grant. I think I would bring to the conversation a better understanding of the context of what the conversation might be about. There’s a new terrific new annotated memoir of Grant by Elizabeth Samet, who is a professor at West Point. She did a terrific job, and so I think I would know more of what to talk about with him. I’ve been reading American history and military history since I could read, so I don’t think I would just sit there like a dummy. Anyway, I don’t think my French is good enough to talk to Joan of Arc. It’s pretty good, but it’s not that good.