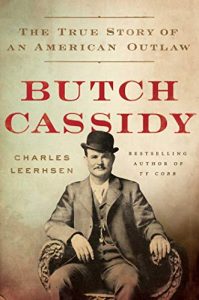

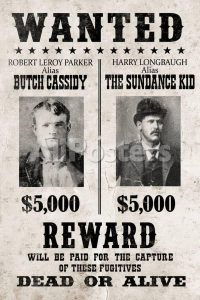

Author and journalist Charles Leerhsen has made a career out of chronicling the lives of some very famous and complex men, from Chuck Yeager to the renowned race horse Dan Patch. His last book, the award-winning bestseller “Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty,” shattered over a century of mythology around the baseball icon, leaving readers with a far more interesting and nuanced version of the man than anyone had ever presented before. His new book does the same for the man born Robert Leroy Parker in Utah in 1866, but who the entire world came to know as Butch Cassidy. We sat down recently to talk about “Butch Cassidy: The True Story of An American Outlaw” and the epic struggle to find the truth behind the legend.

Author and journalist Charles Leerhsen has made a career out of chronicling the lives of some very famous and complex men, from Chuck Yeager to the renowned race horse Dan Patch. His last book, the award-winning bestseller “Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty,” shattered over a century of mythology around the baseball icon, leaving readers with a far more interesting and nuanced version of the man than anyone had ever presented before. His new book does the same for the man born Robert Leroy Parker in Utah in 1866, but who the entire world came to know as Butch Cassidy. We sat down recently to talk about “Butch Cassidy: The True Story of An American Outlaw” and the epic struggle to find the truth behind the legend.

Open Mic: Your new book, “Butch Cassidy: The True Story of an American Outlaw” is out. Cassidy is one of the most enduring figures of the time we call the Wild West, but he’s certainly not the only one. How did you choose him as the person to write about?

Leerhsen: I don’t know if this will be a disappointing answer, but I had him chosen for me. I was casting about for a new project after “Ty Cobb,” and my editor suggested I do a book on Yogi Berra. I actually worked on it for six months, but Yogi just didn’t intrigue me. So I was really down in the dumps and wondering what to do when my editor suggested Butch Cassidy. It was his enthusiasm that got me to do it. I didn’t know anything about western history, though I do have this fascination with the late 19th Century and the early 20th Century, the time between about 1880 and the first world war. I think that is the most important and interesting time in American history. I think there were even more innovations and technological advances in that time than over our last 30 years, and they also led to a wave of social advances. Just the explosion of literacy, which is often overlooked, was a boon that allowed for the explosion of advertising and propaganda and in the way that people looked at themselves and decided what they wanted in life. Butch Cassidy plugged into all that. He also was involved in western history in the sense that he was pushing back against the large corporations that were moving into the west and dominating people’s lives. And often ruining people’s lives. The big cattle companies, the banks and the railroads were tempting people out west with false promises of how easy and good life was going to be and then charging them exorbitant rates for loans and for shipping them their cattle and feed, just exploiting them in every possible way. So life in the west was actually pretty miserable in a lot of ways. He was a part of all that.

Leerhsen: I don’t know if this will be a disappointing answer, but I had him chosen for me. I was casting about for a new project after “Ty Cobb,” and my editor suggested I do a book on Yogi Berra. I actually worked on it for six months, but Yogi just didn’t intrigue me. So I was really down in the dumps and wondering what to do when my editor suggested Butch Cassidy. It was his enthusiasm that got me to do it. I didn’t know anything about western history, though I do have this fascination with the late 19th Century and the early 20th Century, the time between about 1880 and the first world war. I think that is the most important and interesting time in American history. I think there were even more innovations and technological advances in that time than over our last 30 years, and they also led to a wave of social advances. Just the explosion of literacy, which is often overlooked, was a boon that allowed for the explosion of advertising and propaganda and in the way that people looked at themselves and decided what they wanted in life. Butch Cassidy plugged into all that. He also was involved in western history in the sense that he was pushing back against the large corporations that were moving into the west and dominating people’s lives. And often ruining people’s lives. The big cattle companies, the banks and the railroads were tempting people out west with false promises of how easy and good life was going to be and then charging them exorbitant rates for loans and for shipping them their cattle and feed, just exploiting them in every possible way. So life in the west was actually pretty miserable in a lot of ways. He was a part of all that.

Open Mic: Much like Ty Cobb, there is an entire mythology built around Cassidy. How different was the real person from what we think we know about him?

Leerhsen: Butch Cassidy had a different history than some of the other major western figures in the sense that he wasn’t discovered by Hollywood until relatively late. And when he was discovered, he had fallen into obscurity. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were not written or even thought about much before the movie of the same name came out in 1969, outside of the intermountain west (All or parts of Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas). He certainly wasn’t a household name like Billy the Kid or Jesse James. The screenwriter, William Goldman, got intrigued by his basic story, but he didn’t do any real research at all. Neither did Paul Newman, who played Butch to Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid. But the character Newman gave us, which was this incredibly charismatic, charming, witty guy, turned out to be, almost by accident, a lot like how Butch really was.

Leerhsen: Butch Cassidy had a different history than some of the other major western figures in the sense that he wasn’t discovered by Hollywood until relatively late. And when he was discovered, he had fallen into obscurity. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were not written or even thought about much before the movie of the same name came out in 1969, outside of the intermountain west (All or parts of Wyoming, Montana, Utah, Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas). He certainly wasn’t a household name like Billy the Kid or Jesse James. The screenwriter, William Goldman, got intrigued by his basic story, but he didn’t do any real research at all. Neither did Paul Newman, who played Butch to Robert Redford’s Sundance Kid. But the character Newman gave us, which was this incredibly charismatic, charming, witty guy, turned out to be, almost by accident, a lot like how Butch really was.

If you look at many of the characters immortalized by Hollywood – Wild Bill Hickock, Calamity Jane or whoever – you find out that in reality they were often terrible people that would make you wonder why you were reading a book about them. But the real Butch, who was born Robert Leroy Parker, was a charismatic, funny, lighthearted guy who got into being an outlaw almost as a form of entertainment, like a vaudeville performer. He didn’t kill people, or even hurt them, with one notable exception that I will not spoil for the readers. He also refused to take valuables from passenger or customers of the places they robbed, telling them “we’re here to hurt the bank or the corporation, not you.”

This was all at great personal risk, by the way. In many states, you could be hung for robbing a train, even if you didn’t hurt anyone in the process. That was the power of the corporations and the men who ran them. They could push through laws like that.

Open Mic: What was the most surprising thing you learned about Cassidy?

Open Mic: What was the most surprising thing you learned about Cassidy?

Leerhsen: Well, one thing that surprised me was that Butch may have been gay. There is actually a lot of circumstantial evidence that he was either bisexual or gay. He never had a steady girlfriend or even took a concerted interest in any particular woman. And because of his charisma, there were many men who were attracted to him. Whether it was in a sexual way or not, there were many men who literally fell in love with him because he was such a powerful and charismatic personality. When they all took off for South America, it appears that Sundance and Ethel – who was called Etta in the movie – were probably married and Butch was something of a third wheel. He always lived with them, but in a separate cabin or room. And in all of his letters and communications, he went out of his way to brag about how he was patronizing the whorehouses and that he had contracted the “town disease,” which we can presume was some kind of venereal disease. So all very circumstantial, but it certainly surprised me.

Open Mic: How long did the research take on this project?

Leerhsen: It took me about four years. I made two trips to South America and several trips out west, a lot of times just to be in the places they had been. I had just come off doing the Cobb book, and it was all very different. Baseball players are on teams, and teams have rosters and schedules so I could always know where they were on a certain date and who they were playing. They were in big cities at a time when there were still a lot of newspapers, often many in each city, so there was always something being written about them that I could dig up. But outlaws were going out of their way to hide their identity. On top of that you have the western press, which was insanely sensationalist and incompetent in how they covered these guys, which made it very hard to trust what was said in the newspapers about them. Butch Cassidy was reported to have been shot and killed more than 50 times, or he would be described as being a fat man with a mustache, of course none of which was accurate.

Fortunately, he did write some letters, which was very helpful. And there was a book that came out in 1939 from a man named Charles Kelly called “The Outlaw Trail.” It was the one time in between Butch’s lifetime and when the movie came out that focused on his life. It’s a hard book to read – it’s not well organized – but in the time he was doing his research there were still a lot of people alive that had encountered Butch and Sundance. Kelly was able to get their statements down, and that was extremely useful to me. There are a few other reputable books since then as well. He also passed through the legal system, so there was a record of him the Wyoming state prison system. So it was difficult, but it was also fun and interesting to go Argentina and Bolivia. The movie simplifies things by leaving out the Argentina chapter of their lives, but it was actually very interesting.

Open Mic: What’s the most challenging aspect of doing a book like this: the research component or getting people interested in a subject they may already feel they know well?

Leerhsen: It’s all challenging. I say this not to be cute, but don’t know how to write a biography. Every time I have to stumble through the process and figure out how to do it again. It used to cause me more anxiety than it does now, because now I realize that’s just the way it works. And I’m kind of glad that’s the way it works for me because I think the other way is the road to hackdom. You always face the same issue – you want the story to be entertaining but you also want it to be accurate. If you picked someone’s name out of a hat and said ‘I’m going to write a biography about this person,’ it could get done but it probably won’t be very interesting or engaging to most other people. So you are always battling with the idea of how interesting you can make the person without distorting the truth. It’s morally wrong to distort the truth, and it also makes the story harder to write. You have to let the chips fall where they may. That’s a lot easier than twisting things to make something fit your preconceived notion.

Open Mic: The movie “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” is so iconic. Does the lasting impact of that movie help or hurt a project like this one?

Open Mic: The movie “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” is so iconic. Does the lasting impact of that movie help or hurt a project like this one?

Leerhsen: There’s no way you can say the film doesn’t help. Like I said, those guys had fallen into obscurity. There are obscure biographies written about obscure people, but that’s what it would be. If that movie hadn’t been made, the story wouldn’t be something that the general mass audience is aware of. In the book I was also able to bounce the characters off those in the movie. I was able to remind people who Butch really was against how Paul Newman portrayed him. There are also other movies and TV shows that derived and picked up interest in them from the movie, otherwise they wouldn’t have existed. I don’t think the average person would have even heard of Butch Cassidy in 2020 if not for the movie. It put him on the map and made him a household name.

Open Mic: You told me after the Cobb book came out that a lot of people in his world were helpful because they wanted to see a more thorough accounting of his life be out there. How was it this time? Did you encounter any resistance from those who might just want to see the legend still be taken as fact?

Leerhsen: When the movie came out in 1969, it inspired a lot of interest in people to do research into these guys and to become amateur Wild West historians. The baby boomers were young and impressionable, and they got very interested in knowing more about these guys. It also inspired this boom in tourism, with all of these Butch Cassidy motels and bars put up in places where he was alleged to have been but probably never was. There would be these conferences where people would go to dressed up like a cowboy to deliver a paper on “the real Ethel Place” or something like that. But now that has subsided. Time has worn that down. Little kids don’t grow up playing cowboy any more.

The scholarly surge now has boiled down now to a bunch of cranky old men, although I did encounter at least one very cranky old woman along the way as well. Like I say in the book, even though they’re Butch Cassidy specialists themselves they try to discourage you by saying things like, “He was just an outlaw. It’s not like he busted trusts in the U.S. or freed the slaves or anything. He was just a ne’er do well.” And then they’ll try to research him out of every incident event he was ever in to prove he was not really part of this robbery or that robbery, until you would think he wasn’t even an outlaw. So it’s a smaller group than it used to be, and a crankier bunch.

Open Mic: Why do you feel we have such a fascination with outlaws and gangsters in this country?

Open Mic: Why do you feel we have such a fascination with outlaws and gangsters in this country?

Leerhsen: It’s not just this country. There are a whole lot of populist outlaws from a lot of countries going back centuries, from Robin Hood in England to Ned Kelly in Australia. So the concept isn’t new or unique. But when you think of this idea of overthrowing authority and reinventing yourself all on your own, that might be the particularly American – and particularly 19th Century American – part of it. That time is the era of self-invention, and Butch Cassidy is a great example of someone who reinvented himself. He gave himself a different name and a persona with specific rules to follow. We’ve always liked these types who snub their nose at authority because it’s fun to think about us doing it too. We tell ourselves these guys are the guys that we would have been if we hadn’t got married at 21 and started having children. So whether they are bedeviling the king in France or the Union Pacific railroad in America, it was great because the railroads were screwing people over. They were better than politicians because they were actually doing something about it. One of Butch’s friends once said that Butch helped more people than FDR, and with less red tape.

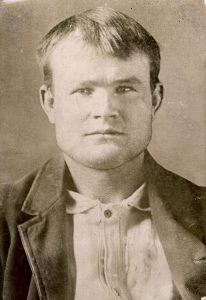

Open Mic: Clearly you believe they died in that gunfight in Bolivia. How did you filter through all of the claims that they survived and died many years later back here in the states?

Leerhsen: Yeah, the movie chickens out and just has them making a run for it. You hear the gunfire and presume all is lost, but you don’t really know. The real story is that they did die in Bolivia in 1908 under an assault from the authorities, but they didn’t die the way you might have expected them to have died. I don’t want to ruin it for anyone who hasn’t read the book yet, but they died in a rather startling way. All the evidence is circumstantial because we don’t have their bodies, but the circumstantial evidence is very strong.

The Bolivians were very bureaucratic in the sense that they held a lot of hearings and inquiries afterward to determine the facts. The assault was carried out by a Bolivian militia, so there were official incident reports filed. Butch and Sundance were in possession of certain items from a robbery they had carried out a few days before, including part of about $200,000 in American currency from that heist. Taken in total, it’s overwhelmingly obvious that they were the men killed in that assault. But as we were just talking about, the allure of outlaws is like a coiled spring. It needs to get released, and part of that is the construction of a story that they didn’t actually die that way, that their deaths are just another story the authorities want you to believe.

In Butch’s case, there were reports until the 1940s that he’d been spotted in Nevada and Utah and various other western states. I talked with the grandson of L.V. Lay, who was a part of the Lay’s potato chip family and Butch’s actual best friend, and he swore to me that in the 1940s his grandfather pulled up in a car and intimated that the person in the passenger seat was Butch. So even this person believed it. It wasn’t true, but it’s no different than what happened with Billy the Kid, Jessie James, Elvis, JFK and others who die suddenly and unexpectedly. They develop this post-death myth that refuses to accept they are gone. As a researcher, once you understand that’s how it is, it’s a lot easier to let that kind of thing roll off your back.

Open Mic: You ghostwrote one of Donald Trump’s books, and have since become one of his harshest critics. Given how polarized we are as a society right now, many writers are avoiding making any kind of public political statements out of fear it will drive away half their readers. As Michael Jordan once famously said, “Republicans buy sneakers too.” Does it concern you at all that being so open in public could hurt your sales?

Open Mic: You ghostwrote one of Donald Trump’s books, and have since become one of his harshest critics. Given how polarized we are as a society right now, many writers are avoiding making any kind of public political statements out of fear it will drive away half their readers. As Michael Jordan once famously said, “Republicans buy sneakers too.” Does it concern you at all that being so open in public could hurt your sales?

Leerhsen: No. I think we’re beyond the “Republicans buy sneakers too” thing. I don’t think this is about being a Republican or a Democrat. I think it’s a cult thing. We’ve gotten down to the moral nitty gritty here. It’s funny, because with the Cobb book I ended up becoming a hero to right-wingers because people on the right like to hear the message that someone isn’t a racist. They think that word is used to often. They think they’re not racist, so they liked to hear that Ty Cobb wasn’t racist. By extension, they hear me saying that baseball wasn’t that racist and the world was not that racist, although baseball and the world was in fact almost comically racist. My point was that Cobb himself was not the racist monster he was portrayed to be.

But the short answer is no. It’s not that I’m rich so I don’t have to care about sales, or that I’m just some really great guy. It’s that we really can’t think like that anymore. A crazy man – an immoral man, an incompetent man, a mentally ill man – is president. You can’t worry about that other stuff.

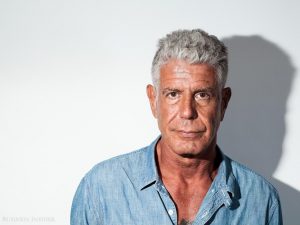

Open Mic: Do you have any new projects you are already working on?

Leerhsen: Yes. I’m deep into working on a book on Anthony Bourdain. It’s been very challenging in that as open as he was about himself – and I’ve not found any instance where he didn’t tell the truth about himself – I’ve found many instances where he didn’t go quite as far with it as he might have. There are also people around him who might have a financial stake in his legacy, and some of them have circled the wagons and don’t want anyone else telling his story. But fortunately, the edicts that went out that no one should talk to me has actually pushed several key people in my direction that don’t want to be told who they can and cannot talk to.

Open Mic: I like to end with a fun question. Let’s say I could put you together with any one person from the following group for a good conversation. This time I’ll offer a variation on my usual collection of options and offer you the chance to speak with any of the historic figures you have written about – from Cobb to Butch Cassidy or even the people around the great horse Dan Patch? Who would you choose and why?

Open Mic: I like to end with a fun question. Let’s say I could put you together with any one person from the following group for a good conversation. This time I’ll offer a variation on my usual collection of options and offer you the chance to speak with any of the historic figures you have written about – from Cobb to Butch Cassidy or even the people around the great horse Dan Patch? Who would you choose and why?

Leerhsen: I guess I would pick Anthony Bourdain. I’m in the process of discovering why the guy who had the greatest job in the world would kill himself, but I’d love to hear his version of the story. I think I know what it is, but I’d like to hear it from him. I also feel like I know him to some extent, though I’ve never met him. And I think I’d rather meet Dan Patch than the people around him, so I’ll definitely take Bourdain.