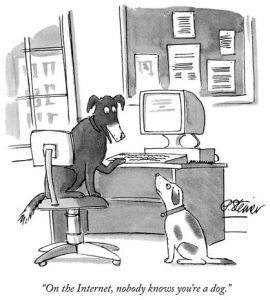

Peter Steiner has always found ways to tell stories. His first cartoons appeared in the New Yorker in 1979, and his 1993 “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” cartoon remains the most popular in the magazine’s history. He is also a gifted artist whose paintings regularly appear in galleries around the New York area. And for the last decade he has turned his attentions to writing the “Louis Morgon” suspense series, which has been favorably compared by many reviewers to the works of Graham Greene and John Le Carré. His latest, “The Good Cop,” departs from Morgon to establish a new hero trying to do the right thing in a world that is increasingly gone mad. I sat down with him recently to talk about his breadth of work and the process of storytelling.

Peter Steiner has always found ways to tell stories. His first cartoons appeared in the New Yorker in 1979, and his 1993 “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog” cartoon remains the most popular in the magazine’s history. He is also a gifted artist whose paintings regularly appear in galleries around the New York area. And for the last decade he has turned his attentions to writing the “Louis Morgon” suspense series, which has been favorably compared by many reviewers to the works of Graham Greene and John Le Carré. His latest, “The Good Cop,” departs from Morgon to establish a new hero trying to do the right thing in a world that is increasingly gone mad. I sat down with him recently to talk about his breadth of work and the process of storytelling.

OM: I’m reading The Good Cop now, which I am really enjoying. The book’s backdrop is the rise of Hitler and the Nazis. How much did current events play into this storyline for you?

Steiner: It was a very important part of it. In fact, I can’t remember exactly when the idea for the book started percolating in my mind but I’m fairly certain it was around the time of Trump’s election. I used to be a German scholar of sorts and so I knew something about what happened in Germany in the 20’s, and his election just rang a bell for me and made me want to write about what could go bad in a situation like this. So, the short answer is, almost everything in this book has been about what’s going on now.

OM: Your Louis Morgon series has been compared favorably with the works of John le Carre and Graham Greene. That’s pretty heady company. Does that kind of comparison ever have any impact on you when you sit down to write?

Steiner: I don’t know about subconsciously, but consciously it certainly doesn’t. I was a literary scholar and I studied German literature in the 19th and particularly 20th centuries, and those are more my models for how to write. When I’m writing, I’m kind of aware of that history in my thinking but not at all aware of comparisons that others have made. Even though I find it very complimentary, I don’t take it too seriously. These are people writing literary critiques or reviews or blurbs, and if they like a book they want to say something nice about it so they make a comparison like that. But I don’t regard it as somehow true. It doesn’t do much for me except make me feel good.

OM: Do you intend for the new book and your lead character Willi Geismeier to also be a series?

Steiner: It looks like it will be at least two books. The publisher said they were interested in having another book, and I think this one is sufficiently good and Willi Geismeier is a sufficiently interesting character to go on with him. And the situation he finds himself in of course is fraught, so there’s a lot of material there.

OM: I really admire the breadth of your creativity – a successful artist, cartoonist and novelist. How do each of these very different interests complement one another?

Steiner: They seem to use different parts of my brain and of my character. As I’ve been painting, I would often be mulling over stories in my mind, and one of them would kind of congeal into a genuine idea and then I would write a novel. As you know, there’s a lot of description in a book and a lot of visual cues, so as I was writing I would start imagining a painting. So maybe they did feed off of one another, but they came from different parts of my brain and were responses to different inclinations. Painting is more immediate in a way. You dip a brush in some color and put it on the canvas and there is something you can respond to. Writing is a longer form and it just somehow uses different disciplines. That’s not a very satisfactory answer, but I think that’s the best I can do. I think a lot of it is just unknown to me.

OM: I have a friend who has won a Pulitzer for his cartoons, which he approaches as a condensed bit of storytelling. How do you approach that part of cartooning?

Steiner: I always think of the cartoons that I do as little dramas or little plays with one line of dialogue. There is a setting and there are characters involved so it is a bit of storytelling. It’s very different storytelling from writing novels because it’s over in an instant, but, yes, it is storytelling.

OM: You are the man behind one of the most famous of all New Yorker cartoons, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” Your current cartoons are pretty political. So often now writers are told to not do anything to alienate half their potential audience. Is it ever a concern for you that you might tick off someone and lose a potential reader?

OM: You are the man behind one of the most famous of all New Yorker cartoons, “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.” Your current cartoons are pretty political. So often now writers are told to not do anything to alienate half their potential audience. Is it ever a concern for you that you might tick off someone and lose a potential reader?

Steiner: No, it’s not. First of all, I don’t have huge numbers of readers or followers of my cartoons, which just appear on a blog and a little bit on Facebook and Twitter. And all cartoons are supposed to be offensive. They should be a little bit disruptive and transgressive. So, yeah, I guess I don’t worry about that.

OM: Were you also always interested in writing? What moved you to start writing novels?

Steiner: I was not always interested in writing, but once I started reading great literature professionally, which means critically, and trying to discern what was going on, I got interested in it. I wrote some short stories when I was in graduate school and after that when I was a teacher, none of which were published. But I still didn’t think of myself as a writer or even necessarily as any good at it. But I started keeping a journal when my father was ill. It was a terminal illness, and it caused me to start thinking about his relationship with me and my relationship with him. It wasn’t a bad relationship, but it was interesting because father/son relationships are always interesting, and I kept this journal. I gradually starting fictionalizing the two characters, a father and son, and it morphed into a novel. I showed it to a friend of mine and he was impressed and thought I ought to show it to an agent. I did that, and the agent liked it and took it on. He wasn’t able to sell it, but it got me started. The writing was such a pleasure for me that I immediately started writing another one, and it came easily to me. It’s not that it wasn’t work, but it wasn’t painful work. It was work that I really enjoyed.

OM: Your settings are very akin to a character. Is that a conscious thing? Was it always your intention?

Steiner: I think it’s natural. I’m not a writer who wants people to say as they’re reading it, “oh this is great writing.” I want it to kind of disappear. I don’t want to be an intermediary and obviously explaining, obviously illuminating. I don’t want to do clever stuff. It’s hard to do that because the temptation is always there to show off a little bit, but I want to disappear. One way to make that happen is to have something more interesting than me in the foreground, have an interesting setting, have an interesting set of events, have an interesting set of characters and let them tell the story rather than me telling the story.

OM: Which most often comes first for you – the plot or a character?

OM: Which most often comes first for you – the plot or a character?

Steiner: Oh, the character. The character is everything for me. When I start a book, I usually have a vague idea of where I want it to go, but that’s about all. I may have some sense of what the resolution should be, but I haven’t got any idea of how I’m going to get there. Writing the new one I didn’t even know what the resolution would be. I mean, I knew what the historical resolution was but as far as the characters who were involved, no. I didn’t mean to begin with Willi Geismeier, who was not supposed to be the main character. Maximillian was supposed to be my main character. I realized what the theme of the book was – about how to remain a good person in bad times – the more powerful person to carry that load was a policeman, so that’s how Willi Geismeier showed up. There was a crime, and his character as he appeared in my mind was sort of magnetic and interesting to me. He’s a little bit like Louis Morgon, that kind of curmudgeonly outsider who doesn’t like the way that things are usually done and develops his own way of doing things and so on. So I guess I write the books in order to know how things turn out.

OM: The publishing industry has changed so much over the last two decades. Do you think things are better or worse now for writers than they were maybe 20 years ago?

Steiner: I really don’t know much about the publishing business, and it becomes more and more mysterious as time passes. The one thing I do know is they’re in kind of a flux themselves, and don’t really know what’s around the corner. The internet and e-books have changed everything, and the business models have changed. Books are products now, they’re not books. They could be cards or toothpaste, as long as they can make money at it. I think many publishing houses are subsidiaries of bigger outfits that really care about the money and don’t really care about the books, so that seems like a huge change. To me it looks worse. This may not be a measure of very much, but it is a measure of something that since the first book, every advance I’ve gotten has been smaller than the one before and has been harder to come by. My agent once told me that unless you’re a superstar it’s actually easier to sell a first book than a fifth book. With a first book people can imagine somehow this is going to be big, and everybody wants big now. But if you have a history of five books, which I had before The Good Cop, then you haven’t paid off. You may have gotten great reviews, which I did, but if you haven’t made money, then they show you the door. And that happened to me.

OM: The one thing all successful writers have in common is they get words on the page even when they don’t feel that big spark of creativity. Do you ever suffer from writer’s block? If so, how do you overcome it?

Steiner: I overcame it before I became a writer. I was a cartoonist and I worked for a newspaper for twenty years eventually doing five cartoons a week, and so I had a deadline every day. I would arrive without an idea and without a clue, but I knew from experience that something would come if I worked at it. And it did, so I don’t experience writers block. Another thing I do as a novelist is when I’m writing I stop writing for the day when I don’t want to, when I want to keep going. If I find myself stuck or up against something I can’t solve, I’ll work until I’m unstuck and at that moment when I’m ready to surge ahead, I stop. So the next day, I can’t wait to get back to it.

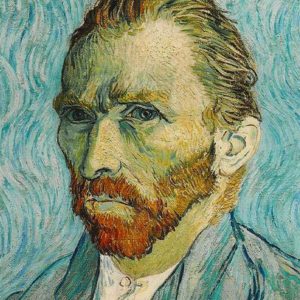

OM: I like to end on what I hope is a fun question. Let’s say I can put you together for a drink and a conversation with just one of the following three people. Who would you choose and why? Your options are Charles de Gaulle, John Foster Dulles or Vincent van Gogh.

people. Who would you choose and why? Your options are Charles de Gaulle, John Foster Dulles or Vincent van Gogh.

Steiner: First of all, thanks for giving me a choice and not making me come up with somebody. I think I would go for Van Gogh. I’m least interested in Dulles because I’m just not that interested in politicians, and Van Gogh is this kind of mysterious being with this fabulous gift that was not recognized in his own lifetime. He’s a tormented and really interesting soul.